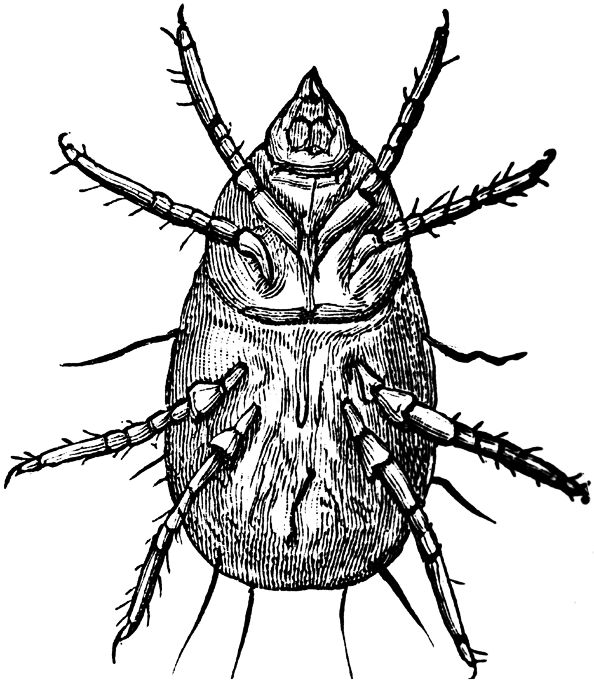

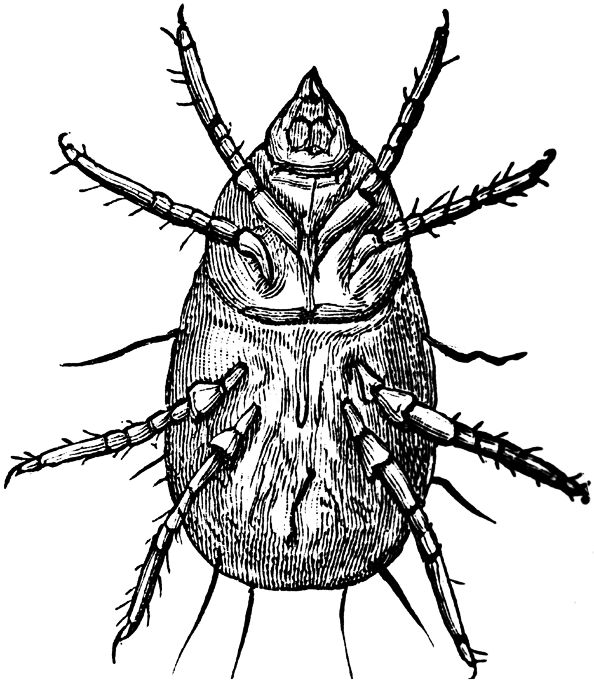

(Flour mite drawing from Clipart ETC of the Florida Center for Instructional Technology (FCIT) at the University of South Florida (USF).

The illustration originally appeared in:

Whitney, WD. 1911. The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language. New York: The Century Co.)

Forgive us for passing on a bad joke about lawyers, but in at least one aspect, mites and lawyers may have something in common. "Ninety-nine percent of lawyers give all the others a bad name." Well, it's not quite that bad with either lawyers or with mites! But, ... |

It's been said that not all mites in a tarantula's cage are necessarily bad, and this is true. The vast majority of mites could not even survive in any tarantula's cage long enough to reproduce. And there are probably many mites that would live peacefully with your tarantula for years with no problems. But, there are perhaps a dozen or so species of mites that have proven to be a real danger to tarantulas. And, the problem is that the average tarantula enthusiast cannot distinguish the good ones from the not so good ones. In fact, identifying mites is an arcane art that has been mastered by very few humans at all! The major problems are that most mites are so tiny, and that there are so many different kinds of them that a lifetime of intense study is required to get a good grip on their biology and taxonomy. There aren't a lot of people with the interest, or the dedication. So, for the novice arachnophiles if not for the afficionado as well, our admonition is that all mites in a tarantula's cage should be considered hostile and dispensed with as quickly as possible for safety's sake. Unless, of course, the science of Acarology fascinates you! |

The mites are another branch of the arachnids, the umbrella group that also contains the scorpions and harvestmen among others, as well as spiders and tarantulas. In many ways they resemble the spiders and some arachnologists even think they may be the next evolutionary step beyond them. This similarity causes tarantula keepers a big problem because many common mites flourish in the same conditions in which tarantulas are kept. Furthermore, because they are so much alike, there are few differences that can be exploited to control mites' propensity for geometric reproduction. Generally, what kills mites also kills tarantulas.

There are literally tens of thousands of different species of mites. Some are parasites (e.g., chiggers on humans, sarcoptic mange on dogs and spider mites on house plants), some are predaceous carnivores, many are merely other creatures with which we share this planet. Their individual numbers are unbelievably enormous. During one of their reproductive outbursts the number of mites in an average meadow might easily outnumber all the other multi-celled animals living there lumped together. It has been said that if we were to magically make all of planet Earth disappear except the mites living on and in it, we might be able to see the ghostly outlines of the continents, the forests, the mountains, even in some cases, individual animals or plants, merely from the mites that they supported. (It is interesting to note that the same thing has been said about nematode worms!)

Mites of many different species are living on and in our pets, the vegetables that we bring home from the grocery store, the soil in our flower beds, the birds that visit the bird feeder in the backyard and even on us without our knowledge or consent. Mankind has been living with mites since first evolving several million years ago. In fact, the mites almost surely predate mammals. We've been living with them through all our history and all our lives. They were here first. They're eminently good at survival. They're multitudinous. They're fecund. They are everywhere. There is no escaping them, they're part of life on Earth. But usually mites only occur in very small numbers because life for them is harsh and they die by the billions.

The mites that infest tarantula cages are not specific tarantula parasites or pests. They are a generic species of mite (actually probably several species) that takes advantage of any and all hospitable living conditions to live and breed. Enthusiasts aren't certain about how mites kill tarantulas, only that they do and that everyone who keeps tarantulas must do whatever is necessary to keep the mites from enjoying the reproductive frenzy that they excel in lest they lose valuable pets.

Cricket farms are engaged in endless combat against mites. Fully half their payroll is spent in the name of mite suppression. But, the mites exist in the billions, reproduce in the trillions and are perpetually on the march. For every adult mite that is destroyed there are literally dozens hatching to take its place. Eradicate them from a cage or even an entire building and within hours, certainly days, they will have reinfested. Most important to this discussion, each of the crickets that we feed our tarantulas arrives with a small but definite compliment of mites or mite eggs on its body. Every time we feed our pets we reintroduce another seed colony of mites. Our problem isn't the mere presence of mites, it's a mite overgrowth, a mite population explosion. We can't eliminate them. All we can do is control their numbers by proper husbandry and care practices. Once we understand these basic facts we can deal with mites effectively. |

The most obvious difference between mites and tarantulas, for the enthusiast's perspective at least, is that mites are extremely tiny and (by comparison) tarantulas are enormous! And, it turns out that this provides almost the only means of controlling the mites' numbers.

Tarantulas are massive creatures with comparatively huge reserves of water in their tissues and thick exoskeletons that are nearly impervious to water loss. Thus, not only do they not lose a lot of precious water through their skins, they have large reserves to help carry them through relatively long, dry periods.

Most mites, on the other hand, are minute. In many cases the size of the entire mite is comparable to the thickness of a tarantula's exoskeleton alone. Therefore, a mite's exoskeleton is an extremely thin membrane and loses water with reckless abandon. Because they are so small they have very little water stored in their bodies. They can mummify in minutes if exposed to dry air, and a mummified mite doesn't reproduce.

This should immediately suggest a way to promote the survival of our tarantulas and suppress the reproduction of mites, the foundation for our basic technique for caring for tarantulas: Keep the cage as dry as possible to retard mite population explosions. But, because tarantulas must have some source of water to drink or eventually they'll die too, supply the tarantula with a water dish. Virtually all tarantulas will soon learn where the water dish is and what it's good for.

Being orders of magnitude smaller and much more liable to dessication, mites aren't anywhere near so lucky. Finding a water dish in a cage is a chancy endeavor for something as minute as a mite. Climbing the side to get at the water is a major expedition. In an arid cage, most mites die of desiccation long before they can grow and reproduce.

Like in-laws and the neighbor's cat, we can never really get rid of all mites permanently. However, we do have a fairly good method for monitoring mites' numbers in our cages. Merely make a regular practice of performing a middle-of-the-night mite inspection once a month. If we are keeping members of the "swamp dwelling" tarantulas (e.g. Theraphosa blondi, the goliath birdeater), we should perform the test much more frequently, perhaps once a week.

In the middle of the night, after the lights have been out for several hours, get up without turning on the room lights (which would interfere with our night vision) and shine a common flashlight through the side of the cage while looking carefully through the front. Can microscopic points of light be seen slowly moving over the substrate, ornaments or across the cage walls? If so, we've just spotted our first mites. If not, look around the water dish or any food remains. Be patient and look quite closely for any signs of movement. If nothing is seen, smile blissfully and go back to bed.

Another strong indicator of a mite infestation is a small raft of what appears to be transparent, granular dust floating in the water dish. These are a few of the hordes of mites in the cage that were lucky enough to find the water, but unlucky enough to fall in! The discovery of such a raft should immediately precipitate at least a midnight inspection if not an immediate cleaning.

If no mites are apparent we're most fortunate. If we're really paranoid and want to clean the cage anyway, or if the cage is developing an odor, all we need do is a standard cleaning.

Don't forget to secure the cage cover. The tarantula has just had its world literally turned upside down and it may not recognize it's cage. For several days it may roam about extensively, maybe hang from the cage walls. We don't want it to escape during this trying time. Also, don't feed the tarantula for at least a week after cleaning its cage. It doesn't need the added insult of a bunch of rowdy, mite laden crickets terrorizing it too. Give it a little quiet time to become accustomed to its new setup before offering dinner.

If no mites or only a very few mites are found, a minor cleaning and a change in husbandry practices may be all that's necessary to avoid a major plague. If a full blown, rampant mite population explosion is discovered a more aggressive action is mandated.

If you see mites, especially if they're numerous, you must make an effort to clean the cage as soon as possible. While it normally isn't necessary to do so at three o'clock in the morning, the cage should be cleaned as soon as possible, no later than the very next weekend.

We strongly urge that any and all furnishings that cannot be effectively cleaned with bleach water be discarded, but if there is some overriding reason why this can't be done there is an alternative method for dealing with them. Those items that cannot be washed in the bleach solution might be sanitized in a microwave oven. Chief among these are porous things like wood decorations because they would soak up the chlorine and release dangerous chlorine fumes for the remainder of their existence, items that would be damaged by excessive water like some sandstone formations, or items that would be damaged by the chlorine bleach like colored or painted ornaments.

There are some problems with this method, however. Metal items should never be used in a microwave, even aluminum foil, unless the item is manufactured expressly for the purpose. Especially, look for metal wires in plastic plants. Be extremely cautious about microwaving plastic items lest they melt into a amorphous puddle or catch fire. Some are safe, some are not. Lastly, look for cavities of trapped air or water. If the air or steam in such a cavity cannot escape through a pore or hole, the ornament could explode. In addition to being quite dangerous, setting off such a bomb in your kitchen is considered bad form to say the least. Spouses and house mates commonly take a dim view of the practice!

If the ornament can be moistened, do so first. If not, include a cup of tap water in the microwave to act as a safety "sink" for the microwave energy. Set the oven on "high" and microwave the items for 5 minutes. Watch what's happening in the microwave oven during the process and abort the operation if anything unexpected happens. Moist items or the cup of water should steam a little before the operation is complete.

Allow the microwaved items to cool to room temperature before replacing them in your tarantula's cage.

There are other ways of sanitizing cages and decorations, but most of them are either inconvenient, ineffective, or even dangerous. For instance, these authors have heard of people who baked their cages and substrate in conventional ovens. This can pose a serious fire hazard, and damage plastic and glass cages. It can also raise a powerful stench, an issue about which your spouse or house mate might have an adverse opinion.

Others have used some truly exotic chemicals in trying to quell mite infestations. One such case involved a hospital employee who sterilized her pet's cage and decorations with ethylene oxide when her supervisor wasn't looking! Besides endangering her job, this was largely an exercise in futility because she introduced another population of mites the very next time she fed the tarantula. A good cleaning and a change in care practices would accomplish more.

A topic that occurs regularly on the Internet mailing lists are predatory mites. There are several species of these mites that have been used by enthusiasts to hunt down and eat the offending invaders. The good news is that these actually work. The bad news is that they commonly cost no small amount of money, especially when the courier fees are factored in, and while they work, they are not a permanent solution to the problem. While their expense and bother might be justified for some of the "swamp dweller" tarantulas like Theraphosa blondi, it is almost always cheaper, easier and more effective merely to clean up your tarantula keeping act in the first place.

Another strategy involves using a cotton-tipped swab and either rubbing (isopropyl) alcohol or petroleum jelly. Besides being dangerous to the tarantula (the alcohol, for instance, could kill the tarantula if you accidentally get it into its book lungs), it's also largely ineffective. The few mites that might be removed from the tarantula's exterior are only a minuscule percentage of those that are either too small to see (various immature stages) or hiding deep in the book lungs or crevices in the tarantula's exoskeleton. Don't waste your time and jeopardize your tarantula.

Some enthusiasts have reported some success in giving their tarantulas a shower! They hold the tarantula under a gentle stream of room temperature tap water, sometimes rubbing recalcitrant mites off with their fingers or a soft artist's brush. This will only work with the most gentle, easily handled hand pets (perhaps neither with your goliath nor Usumbura baboon!). And, the stress of being subjected to such abuse can kill the tarantula, especially if it is already near death. Most importantly, it will only remove the few mites that can be seen on the tarantula's exterior, leaving the majority of the hordes to reproduce in the substrate and hidden in the crevices of their host. We do not recommend this treatment except under extreme circumstances.

If matters have progressed to the point where the tarantula is literally crawling with mites, you must work very fast to save your pet. Here, tackling the problem at 3:00 in the morning is clearly justified.

Set up a small cage with only a layer of fresh substrate, escape proof cover and the water dish, nothing else. Move the tarantula into this secondary cage while cleaning the original cage. Do nothing to retard ventilation or retard the drying of the substrate.

Thoroughly clean the original cage with bleach water (see above). Don't forget to clean the cover. Then set it up again with only substrate, cover and a water dish. Again, do nothing to retard ventilation or retard the drying of the substrate. After two days move the tarantula from the secondary cage back to the original cage. Thoroughly clean the secondary cage with bleach water and set it up with fresh substrate. Two days later move the tarantula back into the secondary cage and thoroughly clean the original cage. Switch the tarantula back and forth as many times as necessary to eliminate the mites.

The working principle here is that the mites will move around every night and in their travels a large percentage of them will leave the tarantula and become lost in the substrate. When you remove the tarantula and clean the cage you also remove and discard those mites. After a string of such changes the mite population in both cages and on the tarantula will eventually drop to nearly nothing. This should happen especially quickly because you are doing nothing to retard ventilation or to increase the humidity in the tarantula's cage. The mites will desicate and die in even larger numbers.

To verify this, you should make a practice of checking for mites every evening before moving the tarantula to the other cage. Pay special attention to the tarantula itself. As soon as no mites are evident you may consider it time to set up the original cage as permanent quarters again. Even then you should make a practice of checking for mites in the cleaned cage about once a week for the next several months, just to be sure that the breeding frenzy has been halted.

The fact that you experienced a plague of mites is proof positive that you're doing something wrong in caring for your tarantula. Carefully review your care practices. For instance, the cage is almost surely being kept too damp. The one characteristic that kills all mites is dryness. STOP MISTING (if that's what you do), uncover more of the top to allow somewhat better ventilation, let the substrate dry out completely. Just be certain to supply a water dish!

Because mites thrive in moist environments, those of us who keep the "swamp dwellers" (e.g., Theraphosa blondi or Hysterocrates gigas) are at greatest risk. Consequently, these species' cages must be inspected for mites (and cleaned) much more frequently.

Those experienced enthusiasts with larger collections of tarantulas (Hint, hint. Nudge, nudge.) often adopt the practice of keeping one or more spare cages set up and stored away in a closet, bottom shelf, or other space just in case they detect a mite apocalypse at 3:00 AM. This is an especially good idea if high risk or brutally expensive tarantulas (e.g., swamp dwellers, babies, Poecilotheria metallica) are being kept.

(It has been our experience that such crises never occur until fifteen minutes before we must leave for a concert for which we've spent $150 a ticket, or at 3:00 AM on the morning of a final exam in college level calculus! YOU'VE BEEN WARNED! Be prepared!)

Set a cage up complete with substrate, water dish, hide and other ornaments. Allow it to stand a very few days until the substrate has thoroughly dried out. Then, wrap the cage in plastic food wrap to keep excess dust from settling in it and soiling it. Store it safely away for WHEN NOT IF a crisis arises.

When that magic time that we all dread arrives, all we need do is strip off the plastic wrap, fill the water dish (perhaps dampen the substrate if absolutely necessary), and move the tarantula into its new quarters. Need we remind you that the soiled cage must be cleaned and set up as soon as possible in preparation for the next crisis? (And, there's always a next crisis!)

As Spring approaches, the daylight hours get longer each day. After a long, cold winter there is an indication that temperatures outside will begin to moderate soon. Be forewarned that this is the time of the year when we are at greatest peril of mite plagues. The lengthening daylight hours and rising temperatures can trigger a case of rampant mite reproductivity that puts rabbits and houseflies to shame.

All year long a fresh supply of these varmints have been introduced every time crickets were fed to our tarantulas. And, while almost all die quickly in a dry cage, a very few manage to survive either on the tarantula or in some protected micro-habitat in the cage. Thus, they're already present, just lying in wait. Because many of us aren't as conscientious about keeping our pet's cages as spotless as we might be, there's usually lots of food ready for them as well.

During late winter or very early spring it's time to consider cleaning out your pets' cages. As spring approaches, most tarantulas enter the molting season. Cleaning the cages then will provide a much more desirable place in which to molt, with fewer vermin to reinfest a tarantula right after the molt. That's also our best chance to head off a mere nuisance before it develops into a wholesale plague. If you have any question about whether or not you should clean the cage, you've probably already reached the point where you should. Do it now and avoid the rush.

Jump to the top of this page.

Jump to the motorhome webpage.

Jump to the Spiders, Calgary webpage.

Jump to the Index and Table of Contents for this website.

Communicating with us is easy. Just select here.

Copyright © 2004, Stanley A. Schultz and Marguerite J. Schultz.

Select here for additional copyright information.

This page was initially created on 2004-December-17.

The last revision occurred on 2013-July-03.