Dedication

I Dedicate this book to my parents whom enjoyed the RV

Lifestyle

We would also like to dedicate this book to all

those who dream of going the RV lifestyle and maybe just need a little help along the way.

Preface

Ah the RV lifestyle. Off the grid, no property tax, away from neighbors you seldom liked, and everyday is a vacation. Sounds good,but if your not careful it can be a nightmare.

Everyone has a reason for how they would like to live and how they must live by circumstance. Life has it's thorns like that nice rose that is so beautiful to look at till you grab the wrong spot on the stem and get your surprise. This book is the fifth in a series I planned to write.

With the ever looming

climate change due to use of carbon producing processes, we all need to consider alternatives that help the planet instead of hurting it. Insects and Animals and even Marine species adapt to their surroundings as much as possible, but man kind is like a parasite, it consumes and changes the environment to meet it's needs. Because of these alterations it affects the natural state of the planet and the planet is fighting back. If it doesn't fight back, Earth will become a barren chuck of rock devoid of all life.

We have the knowledge and ability to make the necessary changes now. In this book I will show just one of many doable things we can do. The premise is to stop being a throw away society and become a re-purpose

and restore one instead.

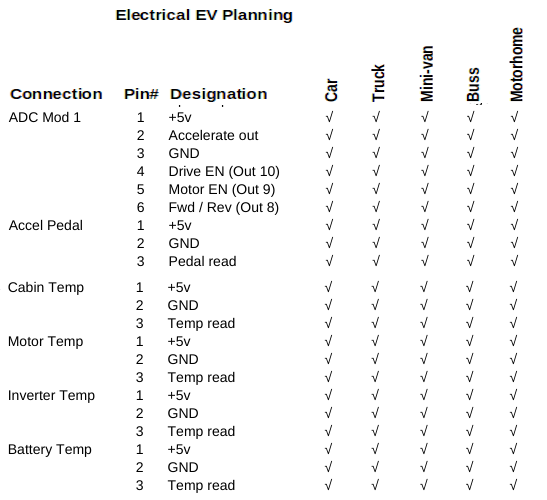

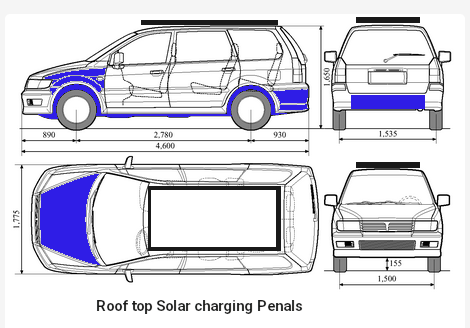

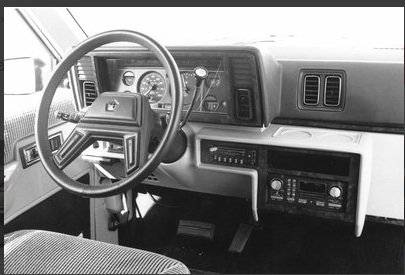

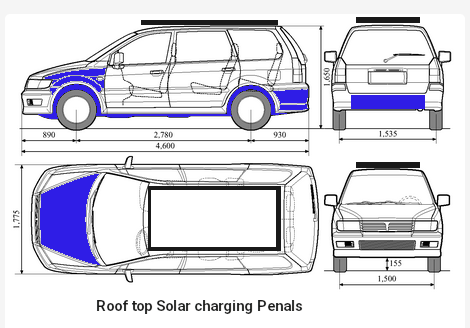

Depicted here is an old 1984 mini-van that would go to the junkyard to sit and rust and over a few 100 centuries return to the earth. It's body is sound but it's engine, catalytic converter, exhaust system are end of life. It is also an environmental disaster in it's current state. There are millions of similar relics in automotive junkyards, farmers fields, lining the side of roads, parked in driveways, or garages and even still in use on the streets.

Depicted here is an old 1984 mini-van that would go to the junkyard to sit and rust and over a few 100 centuries return to the earth. It's body is sound but it's engine, catalytic converter, exhaust system are end of life. It is also an environmental disaster in it's current state. There are millions of similar relics in automotive junkyards, farmers fields, lining the side of roads, parked in driveways, or garages and even still in use on the streets.

Under the governments plan, New vehicles must be EV only by 2030, Used vehicles sold must be EV only by 2035, and all ICE vehicles must be off the road by 2040. We are talking of replacing 24 million current vehicles with electric by 2040. That is 16 short years. The auto makers know the writing is on the wall and are stepping up with new EV offerings. The ICE (internal combustion engine) reign is over.

The move to Green technology by 2040 is a good thing and will see the following changes:

- 24 million cars, trucks, Vans, suv's will become obsolete and replaced by 2040

- ICE Trade-in values drop 50% by 2030

- ICE Trade-in values drop 75% by 2035

- ICE Trade-in values drop to 0 by 2040.

- Quads, snow mobiles, motorbikes, atv's, collector cars will become unuseable

- Class A, B, C motor coaches will be affected as well

- RV travel trailers, 5th wheels, pop-up trailers will need stronger EV vehicles to pull them

- Not everyone can afford to replace their automobile

- Demand for motors, Inverters, Battery packs will increase

- Charging stations will be needed

- 500,000 tonnes of engines, 250,000 tonnes of transmissions will have to be dismantled and melted down

- Job losses in petrochemical, gas stations, Engine Mechanics, and others.

- Gas stations will be gone

- Petrochemical industry will be trimmed back to natural gas, propane, oils for lubricants

- Roadside service will need portable propane generators to help travelers reach a charge point.

- Wreckers and auto-re-cycler businesses will be overwhelmed with cars with no market for the parts

- Lead acid battery makers and re-builders will have loss of market

- Electric grid demand goes up by 200 Million KW per week for Canada.

Some may think it won’t happen hedging on hopes the government will change. Some will refuse to go EV due to reports of poor EV performance until it is too late, and some will protest the changes and the poor trade-in values on their vehicles.

Some local governments have been trying to scare people into petitioning for the

change not to happen siting that we can’t support the demand on the power grid, loss of petroleum revenue and petroleum jobs. But they are just human form of an ostrich that figures if they can’t see the preditor the preditor can’t see them.

Some local governments have been trying to scare people into petitioning for the

change not to happen siting that we can’t support the demand on the power grid, loss of petroleum revenue and petroleum jobs. But they are just human form of an ostrich that figures if they can’t see the preditor the preditor can’t see them.

To address these concerns:

- What if we can convert ICE vehicle to EV instead of scrapping them.

- ICE Trade-in values don’t drop if vehicle can be converted to EV by 2040

- ICE Trade-in values drop 75% by 2035 if the vehicle can’t be converted

- ICE Trade-in values drop to 0 by 2040 if the vehicle can’t be converted.

- Quads, snow mobiles, motorbikes, atv's, collector cars will have to be converted to EV or placed in museums.

- Class A, B, C motor coaches will need to be converted to EV

- RV travel trailers, 5th wheels, pop-up trailers will need stronger EV vehicles to pull them

- Not everyone can afford to replace their automobile

a) Tax free EV savings account

b) Grants or low interest loans to low income workers

c) Trade your ride for converted to EV ride

d) Convert your ride to EV

- Demand for motors, Inverters, Battery packs will increase

a) Conversion centers can source motors, inverters, battery packs and driveline adapters from thousands of wrecked EV in scrapyards.

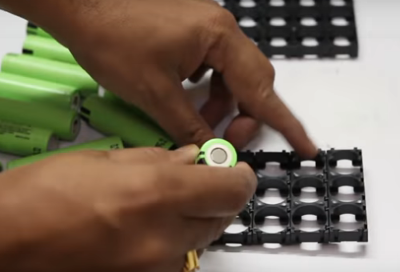

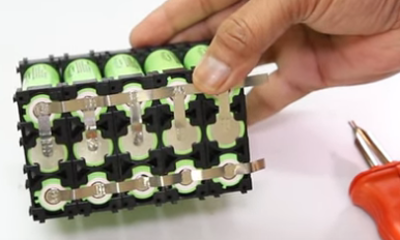

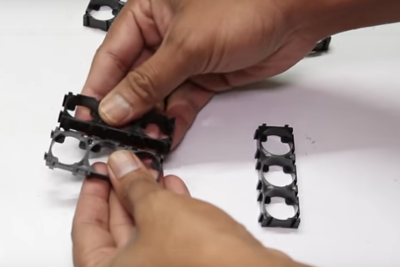

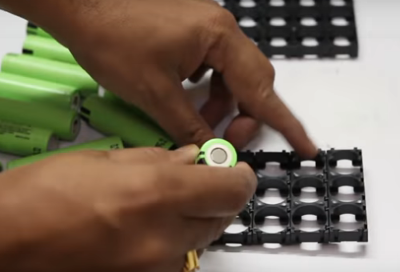

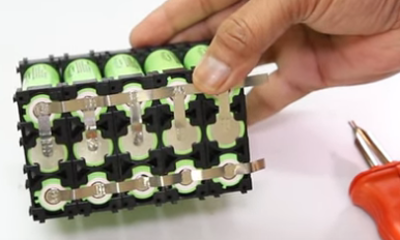

b) New industry to rebuild battery packs into Gcells for EV

c) New industry make driveline parts for conversions.

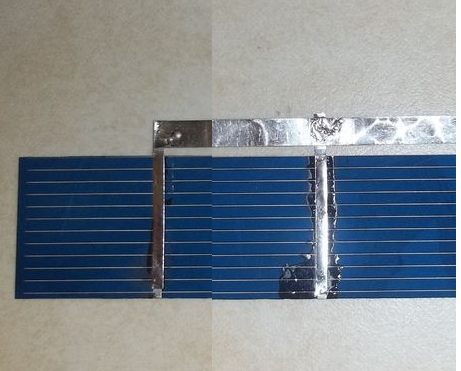

d) New industry make solar panels for new converted vehicles.

- Charging stations will be repurposed gas stations.

- 500,000 tonnes of engines, 250,000 tonnes of transmissions will have to be dismantled and melted down to make new sources of metal.

- Job losses in affected industries will be needed by new industries.

- Gas stations will be repurposed as charge stations.

- Sorry but these greedy industries have been milking every last cent out of people, businesses and governments for at least 120 years.

- Roadside service will need portable propane generators to help travelers reach a charge point.

- Wreckers and auto-re-cycler businesses will be less overwhelmed if vehicles are converted instead of scrapped. Converted vehicles will still need parts so market for the parts remain.

- Lead acid battery makers and re-builders will have new market by making Gcells for EV. Owners can replace worn Gcells just like they do lead acid batteries. Auto makers will need to change from 1 giant pack to 2 smaller packs called banks with each bank being made from user replaceable Gcells.

Gcells can be re-built.

- With solar electric converted vehicles grid demand could be marginally increase by 50,000,000KW per week in summer and 150,000,000Kw in winter

If we do solar-electric conversions most users will not have need for grid power in sunny weather.

With a potential of 24 million vehicles to convert in 16 years that is 1,500,000 a year, 125,000 per month, and 6250 per day so even if we have 26 conversion sites (2 per province/territory) that is 240 vehicles per day to be

- - inspected,

- - rejected and returned to customer

- - remove ICE parts & scrapped as unsuitable

- - remove ICE parts & modified for

motor/inverter/dashboard/battery/solar additions

To me this a great business model, guaranteed work for

inspectors, mechanics, welders, detailers at conversion facilities for 16 years. Partnered with wrecking yards, Solar cell makers, Motor/Inverter makers, Battery makers, and battery reclaimers,

Now imagine taking a car, van, truck that has served you well, and removing that Internal combustion engine and all that goes with it. Replace it with just 3 to 4 pieces that breathe new life into it. No more pollution generation, life span from a mere 5 to 10 years to over 100 years. All the latest luxuries at a fraction of the cost of going new. But in reality it will be better than new. Not a totally fresh idea. We did it back in the 1970's when Electrohome came out with "BTN". "Bring us your old large console cabinet TV with it's aging vacuum tube chassis and we will put a nice new solid state Chassis in it so you can keep your luxury furniture with new life.". So for the car we remove the Engine, Transmission, Exhaust, Gas & Tank, Catalytic converter, Muffler, Starter, Lead-Acid Batteries, and old style dashboard. We put in an Electric Motor with Power Inverter, Lithium Ion Phosphate Batteries, Charge controller, Solar array on the roof, and nice new Digital Dash with built in Navigation, hands free phone, Radio with mplayer, Back-up and Dash cams.

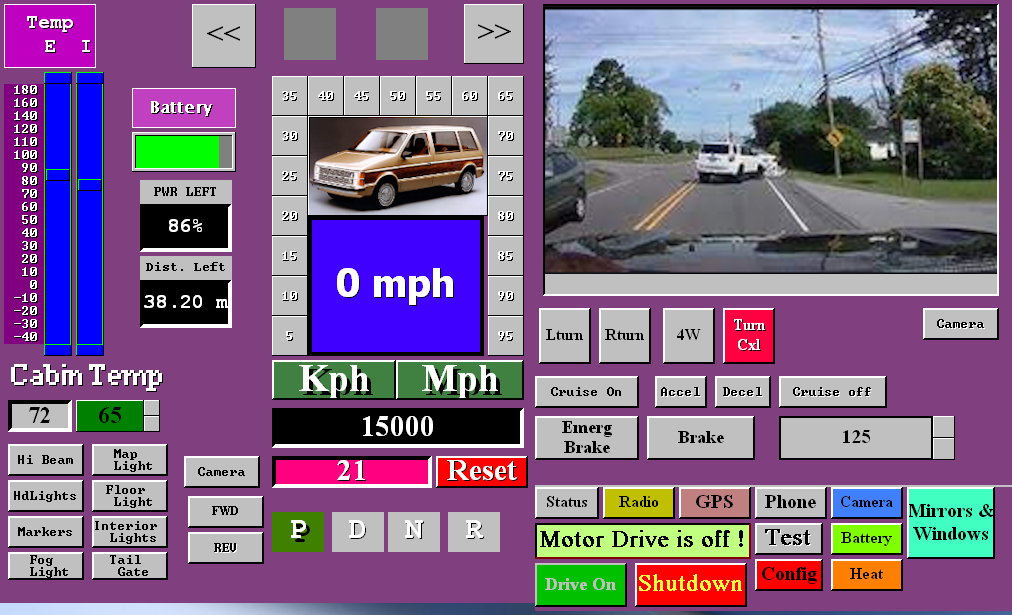

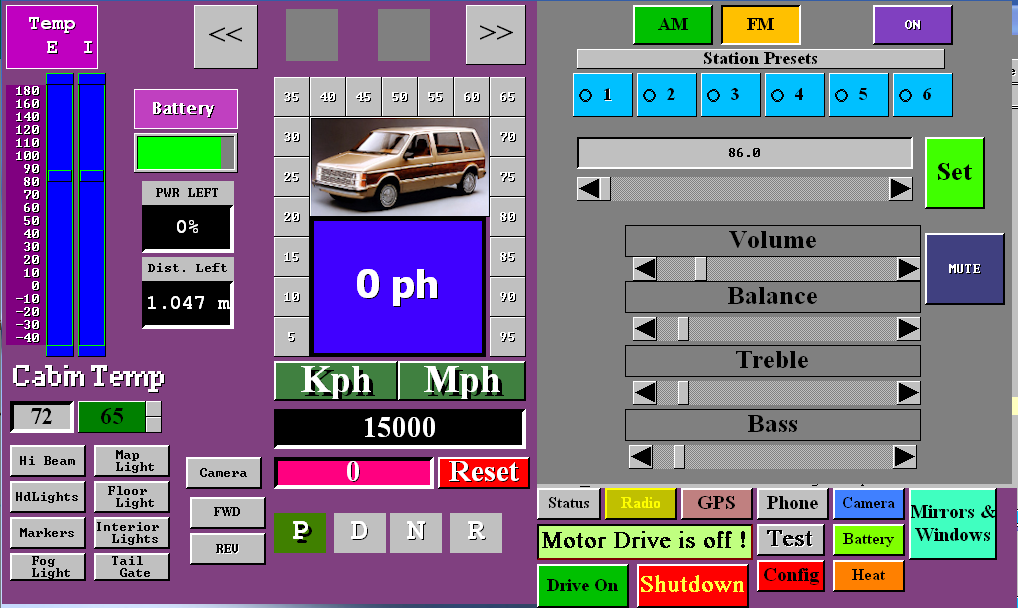

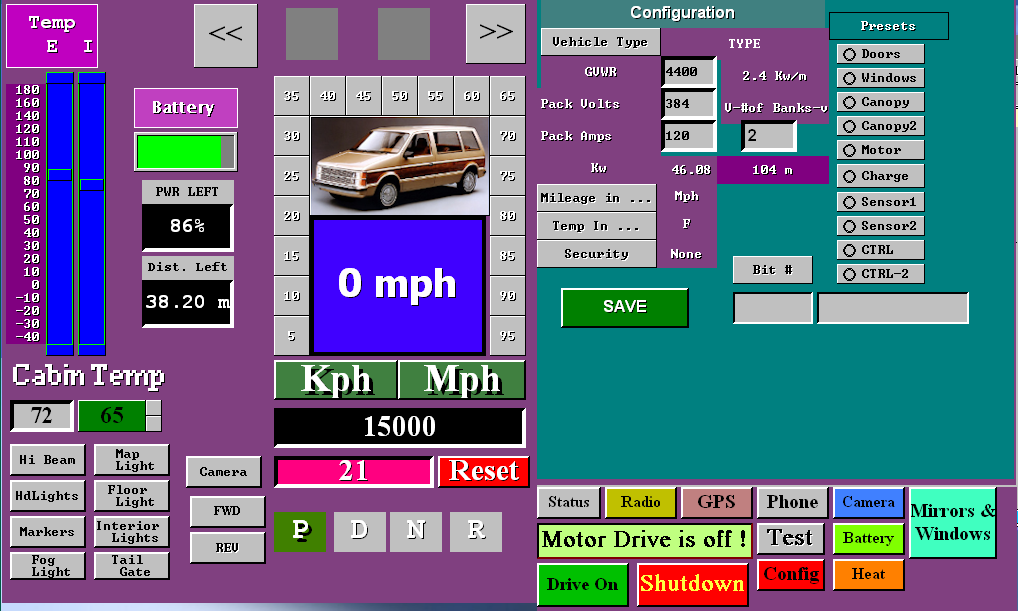

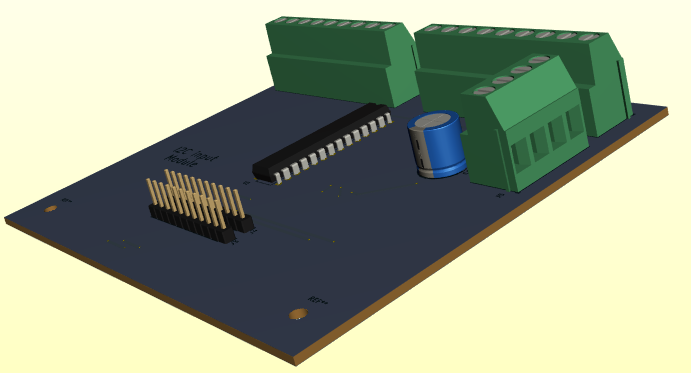

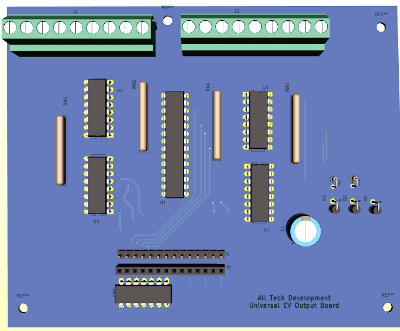

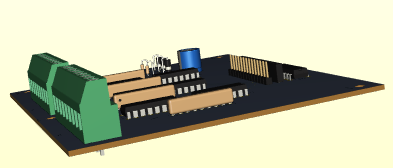

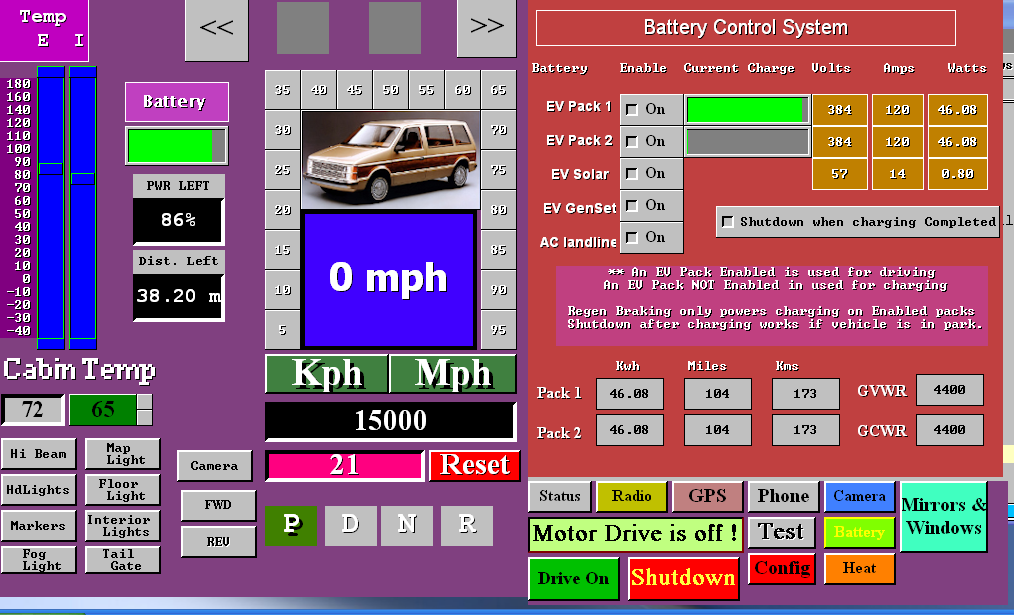

With the Universal EV control system in the following pages, it is hoped that any vehicle of any type can be converted into an electric vehicle. In 16 years we face the prospect of over 24 million vehicles of the ICE (Internal combustion engine) type becoming obsolete. In reallity the 24 million figure is expected to increase by 3% each year. Throughout these pages I will outline in detail what the

problems we face and how to deal with them.

Chapter 1 Choices

Enter a new project

Talking with my accountant friend I

learned of his vehicle troubles. He is trying to arrange to sell and move to a new residence. He has this 38 year old 1984 Plymouth Voyager minivan that he had rebuilt the engine in some 10 years back. Weeks after the rebuild, the water pump failed and he had a local shop do the repair. All did not go well, they had drained the oil and coolant but after the repair only put back the coolant. The oil light didn't come on and he drove it part way home before the motor seized. So there it sits. He offered it to me to convert into an EV but I lacked resources so even though I planned this conversion out here, the vehicle was sent to scrap.

I'll plan for the conversion and

see if at the end it makes sense with it's age. Almost all the things that can go wrong are being replaced in a conversion. The working plans for motor home conversion are easily reconfigured for the smaller minivan.

The pages that follow address this

choice.

Chapter 2 The Grand Plan

My grand plan was to fully document making a solar electric tricycle inclusive of two types of trailer to take it with you while vacationing. That has been done. Fully document making my Class A Motor coach into an EV which has also been done. Now in this documentation I will outline how a mini-van can also be solar-electric.

In the end, I should be pretty much set. My Motorhome with all it's inovative improvements to make my living arrangement ideal. An EV Motorhome to prove it can be done. An EV-custom Trike to provide for short trips at no cost and even less physical effort. An EV-Van capable of doing long trips at no cost. The design and development of a Universal EV control system that anyone can use to convert their gas hog cars, trucks, busses and Motorhomes. .

Chapter 03 Travel for free with an EV Minivan

Wow a big topic fitting for of a book of it's own:

It's high time to move away from the ICE (internal combustion engine) and all that goes along with it. For years I have watched the coming of electric vehicles with hopes of having one myself. I've endured the

hardships of a diesel truck with FICM troubles, Cars with mechanical troubles all related to engines that suddenly just won't run. Even converted a mini-van to run on propane. Then came the Motorhomes which drank gas like crazy at 4 to 6 miles per gallon. After sitting for prolong periods in campgrounds it became a roll of the dice as to whether or not they would start. Having to regularly start them every week just to cycle them so the filters don't seize up or plug. Wasting fuel just so when the time comes they might run. With climate change looming and an EV-Trike being not a great answer for year

round use and long commutes, an EV car or van is the ticket. Mom summed it up right when she said "this is the final straw. You know electronics, you know computers, you have made so many things so you are mechanical, SO WHY HAVE WE STILL NOT GOT AN ELECTRIC VEHICLE."

First off let's try to break it down a bit. An EV conversion of a Minivan is just a smaller version of doing it on a Motorhome. They will all have the same basic fundamental constraints. We are now talking about moving a 1 to 2 ton vehicle at up to 120kph. And where the e-Trike

has a travel span of maybe 50kms we need at least 200 or more kms. Of course you can charge by stopping on route to your destination if you can. But can you afford the time?

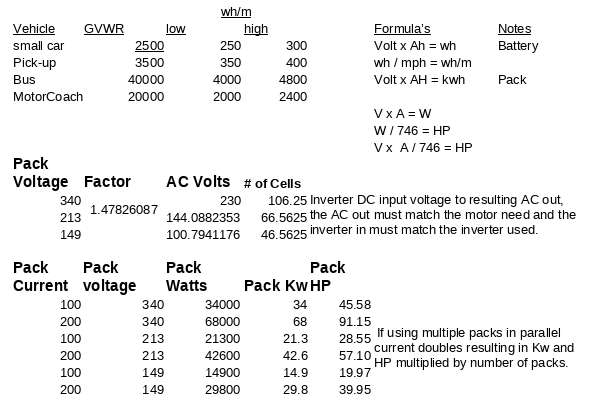

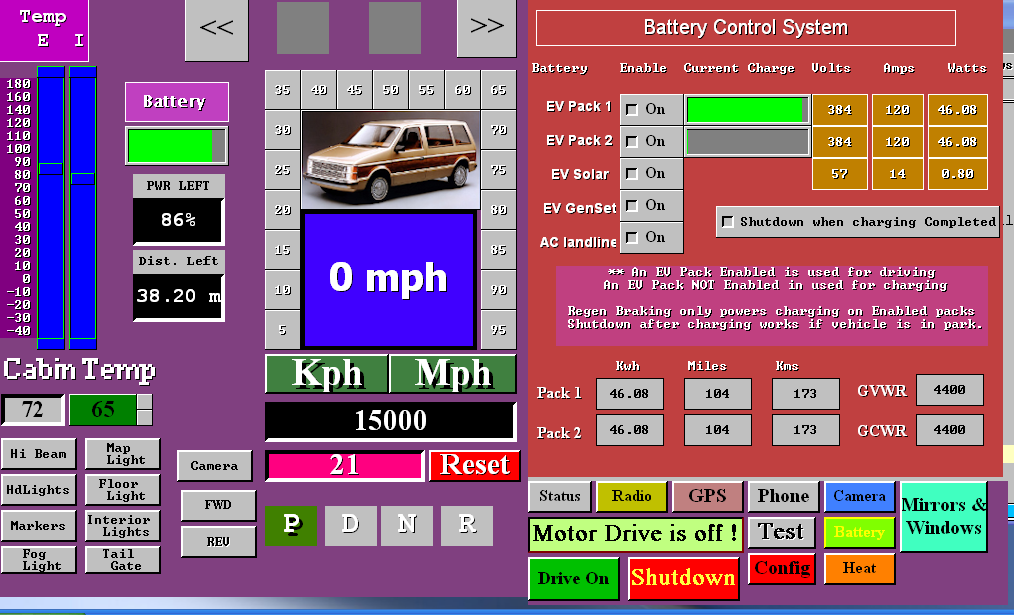

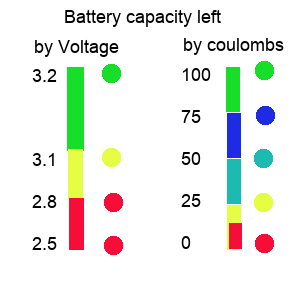

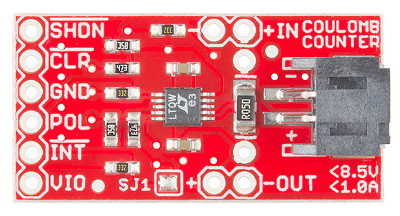

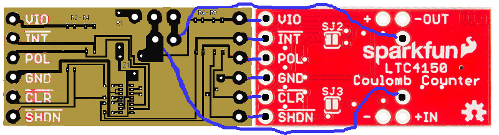

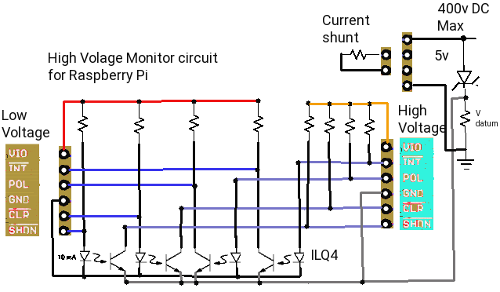

Using the information from the EV-Trike, EV Motorhome, Making custom Batteries, Going solar, Coulomb Counting, and working with high voltage systems, this and subsequent chapters are rewritten with focus on a Mini-Van. Learning from the EV Motorhome, I now know 384v DC battery banks at 300 Amps (115.2KWatts) with an Inverter to drive

a 230v AC Motor is the way to go. Also there should be two or more banks in parallel. With the 48v groups with-in the Banks, I can add solar charging with ease and shore charge from 120v AC much more effectively. Should I suffer a Battery cell dying, my unit will not be stranded without power, as the other bank will provide limited power till I can fix the issue. The original Motorhome plan assumed that the full 600 Amps at 384v DC was being used to drive the Motorhome on a continual basis. But, and there is always a but, if I used 300 to 600 Amps to go a mile total range would be 2 miles at best. This is not the case. The 230v AC Motor working to move a 24,000 lb mass at 2.4Kwh/m says it takes 2.4Kw to go a mile and at 230v AC the current would be 10.43 Amps because P = V * A or A = P / V. Range would be 54 miles pulling a car behind the motorhome and

230v AC @ 1700w/m = 7.39 A or range of 76.23m if just moving the motorhome. For a minivan conversion, we have to move 3400 lb mass at 0.34Kwh/m. Range becomes Battery capacity divided by 0.34 in miles. The minivan is 1/8th the size of the Motorhome in mass. As such, we can't have room for 115kw of battery. We might be able to do 50kw for a range of 50/0.34 = 147miles.

1. Why would you do this Well, frankly for a number of reasons. YMMV. In my journey to being a full time RV er, I don't travel much; but when I do, cost of fuel for distance traveled is an issue. Here is my go to

list of reasons to convert:

- Fuel Tank size : 20gal(72Ltr) at $4.68/gal(1.20/Ltr) = $86.40/Tank** Cost per mile $0.32 if all goes well

- Distance/Tank : 280miles (466km)

- Electric charge: 200A * 120v = 24000watts / 1000 = 24kwh * $0.15 = $3.60 /116km ** Cost per mile traveled cut to $0.05 WOW factor

- More environmentally friendly (no harmful carbon emissions)

- No oil changes

- No Mechanics

- No tows

- Mini-van worth under $1,000 converted for hopefully about $14800 which is by far, 50% cheaper than a new gas hog.

- Unit cost $1,000 + $14,800

- Usage costs :

- @20000km/yr $350

- Maintenance of $0.

- It's only $20,750 over 15 years

In the end replace batteries $14,800 and do it all again.

- Over the lifespan (15yrs) of a typical gas hog

- Unit cost $30,000

- Usage costs :

- @20000km/yr $3500

- Maintenance of $3450. YMMV.

- It's only $52,500 over 15 years

In the end you get to replace your unit and do it all again.

- Most drive trains are rated for 350,000 miles mainly due to engine and associated systems. Take that ICE (internal combustion engine) and all that goes with it out of the equation and replace that with an EV motor, controller, inverter, batteries rated for over a million miles and your now talking progress.

2. Why you should not do this:

- Local gas stations won't like you.

- Gas companies also won't like you.

- The municipalities may worry about what your unit will place on it's power system.

(few understand that 30A 120v AC can not deliver more than that).

- Costs are prohibitive.

- You like paying high repair costs

- You have more money than you need anyway.

- Car dealerships won't be your friend either:

◦ they want to move new models not have people choose to stay with the same old model.

◦ As long as you are running on gas or diesel they know how to talk

the talk and convince you into the nice new unit and know how to

resell your unit.

◦ If it's an EV how do they talk you into a new unit and how do they rate your old unit to resell it.

- You'll here claims that you are hurting the economy and putting people out of work because you

aren't choosing to be broke. aw!

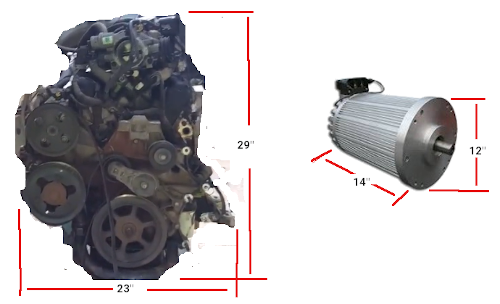

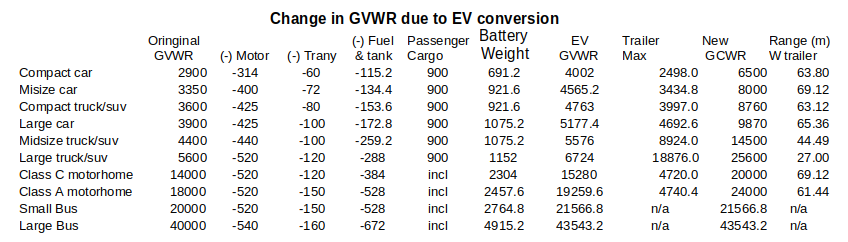

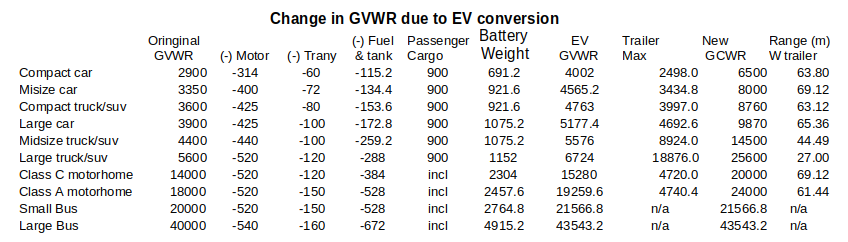

3. What's the first thing you need to consider? Weight:

• You are removing 18lbs of gas tank plus 160lbs of fuel if full,

• about 390lbs of motor,

• 40lbs of exhaust

• for about 590lbs.

• Then you are adding 80 lbs of electric motor,

• Inverter and controller for about another 20 lbs.

Hmm, not bad saving 490 lbs. But, and there is always a but, you need batteries and a lot of them. Lithium ion cells configured into 384v banks @ 100Ah weigh 733 lbs compared to 32x 12v lead-acid batteries of 85Ah at 2720 lbs that's why electric cars use them. Using 2 banks

we can attain 200Ah.

5 yrs ago the cost to do one these conversions spiked at about $80,000. Today it runs about $14,000 and in five years is expected to be about $5,000 or less.

Where do you put all those batteries?!!

How much will they weigh?!!

Can my unit handle the weight?!!

Are all good and necessary questions.

To address these lets look at where to put them.

- In car conversion, limitations of weight and space means that in order to handle the batteries you must give up space, under the rear seat, in the trunk, under the engine compartment hood. And due to weight limits you may not have enough to go very far on a charge.

- Trucks (pick-ups, tractor trailer units) can handle more weight but still may not be enough space for the batteries.

- Buses and other large frame units, have the clear advantage. The frames can handle the weight, space under the frame and where the engine used to be is ample space.

But, and there's always a but, for our Minivan how will it fair. we reduced weight by 503 lbs after adding the Motor. We also remove the lead-acid battery for another 85 lb saving. add back 733 lbs of Lithium battery banks and only have increased weight by 142 lbs!!

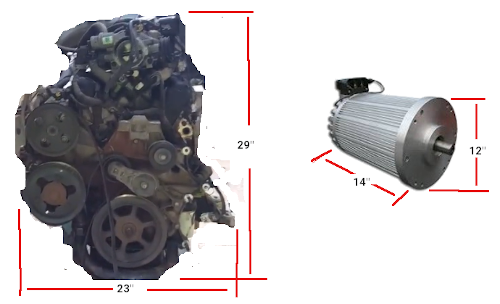

While as it turns out there is plenty of room, A motor to drive a unit our size is only about 10 inches long, 12 inches across. It can take the space formerly used by the engine. The unit fuel tank area can handle 5 cu ft of battery.

Beyond just Motor, Inverter, Controller and Batteries

There are things to note about the differences between an ICE (internal combustion Engine) and an EV (Electric Vehicle):

- Brakes:

Manual work well

Hydraulic work well for lighter vehicles

Boosted hydraulic need electric version of vacumm assist because ICE is gone.

Vacuum weok excellant

Electric & air also excellant

regenerative braking slows you but not that fast

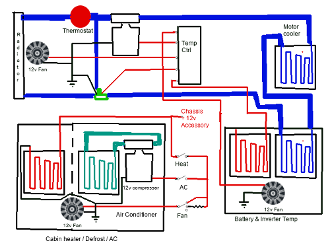

- CoolingHope you planned to keep the radiator because you will need to cool the Inverter and motor.

- Windshield washers/wipers

All vehicles use an electric pump run on demand.

Likewise the wipers are already electric. So for our conversion all we need is to provide 12v power for these systems. That same battery power can run the radiator fan and water circulation system.

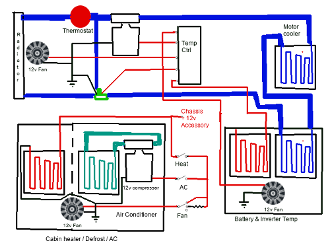

- Window defroster, cabin heat

While rear window defroster is electric so we are ok at the back. We might be able to tap into the cooling line for the motor and Inverter and use a set of salvaged electric ceramic space heaters to create a means of both defrosting the windows and providing cabin heat.

The 1984 Plymouth voyager

has boosted hydraulic brakes using the engine vacuum so we will need an electric vacuum pump.

In an Emergency:

What is all the hoopla about in an Emergency. With a car your moving then you aren't. You may be out of gas, or crashed. Either Way you aren't going anywhere with that vehicle. It all comes in time, years ago there was a big stink about diesel which is a pressurized fuel oil, and Propane or natural gas because of how explosive they can become. Today you still can't park a natural gas or propane vehicle inside a structure, but you can park a diesel inside even though by their own admission it is a greater threat of fire. Because EV battery packs are carefully monitored during charge or discharge you won’t have to worry about this.

For our lowly EV there are just too many misconceptions usually brought on those feeling threatened like auto salespersons, mechanics, people reacting to news and drawing wrong conclusions.

There are hundreds of reports about cell phone batteries and computer batteries catching fire and being so dangerous because they are lithium. This is true but, and there is always a but, There are hundreds of types

of lithium battery. The kinds used in cell phones are rapid charge without BMS or BCT (Battery Monitor System, Battery Cooling Technology). The kind used in EV must be managed by a charge system with BMS and BCT and are of a more stable form

of Battery than a cell phone can have. Temperature is regulated both during charge and normal discharge.

In any accident vehicles have what is known as a inertia switch intended to cut power to the unit and diesel or propane vehicles have a master fuel shutoff as well. For those looking to convert a vehicle to EV, the powers that be have made the following ruling, "An EV of any type must have an inertia switch that immediately cuts power to the motor in the event of a collision. There must also be a master Battery cutoff with clear notification where it is and how to access the batteries for safe disconnection".

In my design, an Inertia switch kills the power to the batteries until reset. A master shutoff is located inside the driver seat area, with notices inside and out where it is. And each bank of Batteries will have a Bank shutoff. I tend to enclose the Banks such that no-one including me can have access to the dangerously high voltages and currents of the battery banks.

The laws:

The legalities are changing daily it seems. As more people turn to evehicles, the provinces and states are re-writing the books. As of this writing I learned that all that required in Alberta is to register the vehicle as an evehicle. It licenses just in the normal sense. No change to drivers licensing rules. The insurance industry is a little behind the times. True they need to know that the evehicle conversion is done right and posses no threat to people property or roadways. For this they ask you to provide a proof of compliance from a vehicle inspection outlet.

At the inspection outlet you can expect them to check things like what have you modified in the structure of the frame, axles, brakes, Emergency Brake, and how have you mounted and secured the motor. Have the battery packs been built to tight transportation safety standards. If you don't pass, expect big problems in the future. As stated above

you must provide an Emergency shutoff with clear notices as to how to disconnect Batteries. And you must have an inertia switch. These things inspectors can fail you on.

Before we proceed...

100 years ago, cars had been around for a few decades but few could afford them. There was almost no gas stations like we have today. Frustration over stations running out of gas and lack of stations prompted many to go back to horse and buggy. Today we have the means to implement EV and in time the infrastructure will be there to make EV's as simple as gassing up your car.

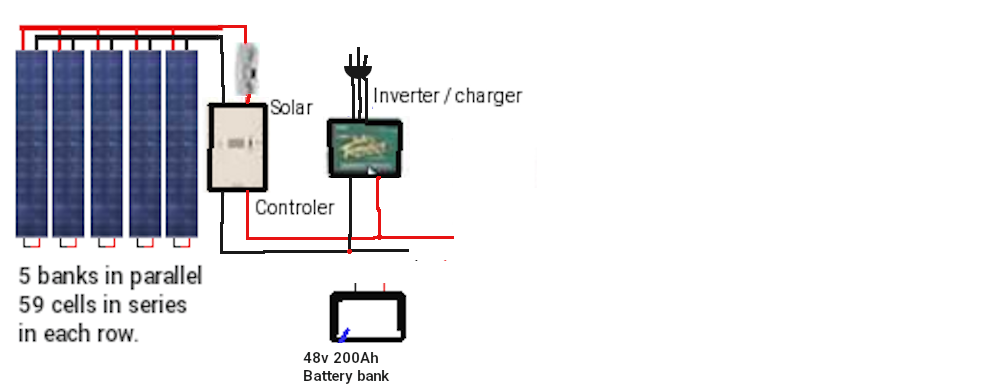

With EV, 15A @ 120v AC charges slow, 30A @240v AC is four times faster and quick charge stations at 360 to 480V @ 100A are few and far between but super fast. It all comes in time. LiFepo4 cells do not do well if charged too fast. a 5A cell should not be charged higher than 5A or it will degrade and fail faster. A 5A cell charged at 5A is known as a 1C charge, 5A charged at 10A is 2C and so forth. When cells are in parallel the charge is split between the cells. So 100A charge to 20 parallel cells is still a 1C since each cell gets 5A. In our plans to start with, we are looking at 2 banks in parallel

with 50 cells in parallel and 8 Gcells of 15 cells in series.

Therefore each pack has 750 cells with each capable of handling 6A. From our 120vAC source we get 15A which when rectified to DC becomes 57v @ 37.5A. Each pack gets 18.75A and because there are 50 cells in parallel in each pack, Each 6A cell is getting a mere 0.37A. The charge system would need to supply 600A @57v to exceed the cells capacity of 1C. If we could deliver 600A charge (6A/cell) it would take 1 hour to charge the cell. Tesla introduced a charge technology that would see a car battery system that would charge in under 30 minutes but what they didn't tell you is that it charges at 3C which is compatible with their batteries but would most certainly degrade other EV car's batteries. Ford now says they can do it in 6 minutes. Sound great, but, and there is always a but, that equates to a 10C charge or 10 times the rated maximum charge rate.

Household charge station possibilities:

From 120v AC 15A source charge time is 16 hours from empty

From 120v AC 30A source charge time is 9.5 hours

From 220v AC 30A source charge time is 5.15 hours

From 220v AC 50A source charge time is 3.10 hours

Now if the battery isn't empty, ie: at 50% the above charge times are cut in half. And if you charge by solar while you work or shop, it would take 60 hours from empty or 7.5 days because the sun only shines an average of 8 hours per day. But it can still have merit. You have used 20% (120A) getting to work and the vehicle sits in the sun for 8 hours in that time you got 80A back into the packs. So when you get home instead of facing charge time for 240A you only need charge time for 160A. In real time you have traded 6.4 hours to replentish 240A into 4.25 hours for 160A. Cost wise at $0.15/kw $1.73 @240A and $1.14 @160A. Either way you are saving over an ICE that eats about $22 @ $1.22 per ltr.

When I first started considering my earlier motorhome project:

I came armed with over 40 years of Electronics experience, Computer science experience, Computer programming experience and some Power electrical

experience. Still I listened to those from many walks of life and perspectives for insight on things I may not have thought of. We are now at the point where the gearheads fought hard to discourage me from going down this path. It's plain Idiocracy. You know if there is something in my long life I

have learned is that it is filled with people who can't or just won't think out of the box. I am going to quote lyrics from a Harry Chapin song here that fits the bill of my point.

The little boy went first day of school, He got some crayons and started to draw

He put colors all over the paper, For colors was what he

saw

And the teacher said.. What you doin' young man

I'm paintin' flowers he said

She said, It's not the time for art young man

And anyway flowers are green and red

There's a time for everything young man, And a way it should be done

You've got to show concern for everyone else, For you're not the only one

And she said: Flowers are red young man, Green leaves are

green

There's no need to see flowers any other way, Than the way

they always have been seen

But the little boy said: There are so many colors in the rainbow

So many colors in the morning sun, So many colors in the flower and I see every one

Well the teacher said

... Well long story short the boy was punished

and later in life he was at a new school with happy

people who painted flowers in all colors and all the boy could do was gruffly say

Flowers are red, green leaves are green, there is no need to see them any other way than the way

they always have been seen.

Here is the point.

- I understand that people who are making their living in the fossil fuel industry don't want to see anything that might take that away.

- Those in product sales like Automotive sales outlets, RV sales outlets don't want a vehicle that lives forever

- Mechanics and automotive parts suppliers also see the drive to go to electric vehicles as a big mistake because that will hurt their livelihood if people don't

have vehicles that will break down.

I don't think I or anybody that I ever associated with wants anybody to loose their jobs or livelihood. People make up facts or false stories to discredit EV as the worst idea to ever come along and this just a sign of short sightedness. The same mechanics that tried to

discourage me from going EV are proud of the fact that they defeated their EGR or catalytic converter to get better gas mileage or more power. Or flaunted how they add nitro to their mix to make a mean racing machine. But I am crazy to find a way that saves money and is legal.

Should I be apologizing because...

- Round trip withgas hog $20 fuel now is likely $3.60 electricity, and $7.67 /day banked towards eventual battery replacement.

- I no longer need oil changes every 3 months or 5km

- My brakes can last over 500,000 miles instead of only 20,000

- My motor lasts a million miles before I need do anything but the gas hog will be screaming for seals, belts, hoses, plugs, additives, and much more at least 5 times over that same period

- Electric generation causes a little bit of carbon emissions and is used by homes and EV recharge, but your gas hog creates enough deadly emissions that if you run it in an enclosed space you kill everyone in that space from carbon monoxide poisoning.

- Yes I can charge at home or find a charge spot elsewhere on my travels and take 4 to 13 hours to get charged vs your gas hog that can be filled up almost at any street corner as long as they haven't run out of gas. It all takes time.

- On a cold rainy day, I can plug in my minivan go in side and stay dry. But you got a gas hog so you got to stand in the rain and get wet and cold to serve your master "the gas hog".

It is my hope that after you read the following pages you will too see the basis for the information I have summarized above.

Chapter 04 An EV Minivan : The Chassis

A look at the chassis a minivan.

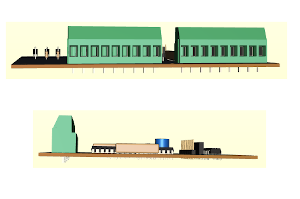

The Plymouth Voyager in 1984 has a 176.574 inch by 69.88 inch wide structure.To do anything meaningful one must work with facts and not rely on assumptions.

The vehicle has a curb weight of 3494 lbs and a GVWR of 4460 lbs.

Here we have the actual historical specs from the 1984 series. It identifies a 32" deep engine canopy and several compartment space allowances. The front canopy will be almost emptied leaving the radiator, fan, lighting electrical, Wash/wipe, coolant resevoir, brake system, steering rack and the CV axles. The engine and it's components, Exhaust manifold, Exhaust piping, catalytic converter, muffler, and fueltank

are to be eliminated.

Here we have the actual historical specs from the 1984 series. It identifies a 32" deep engine canopy and several compartment space allowances. The front canopy will be almost emptied leaving the radiator, fan, lighting electrical, Wash/wipe, coolant resevoir, brake system, steering rack and the CV axles. The engine and it's components, Exhaust manifold, Exhaust piping, catalytic converter, muffler, and fueltank

are to be eliminated.

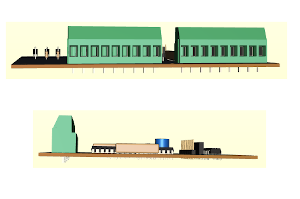

Areas in blue are for the new motor and support systems in the

canopy. Down the left side is the wiring path, and at the rear we have the charge inverter and battery banks.

Areas in blue are for the new motor and support systems in the

canopy. Down the left side is the wiring path, and at the rear we have the charge inverter and battery banks.

The areas in red reflect the items being removed. Engine and support stuff at the front, Exhaust down the right side, and Fuel tank at the back.

The areas in red reflect the items being removed. Engine and support stuff at the front, Exhaust down the right side, and Fuel tank at the back.

Using what I learned from the motohome conversion, If we have 3

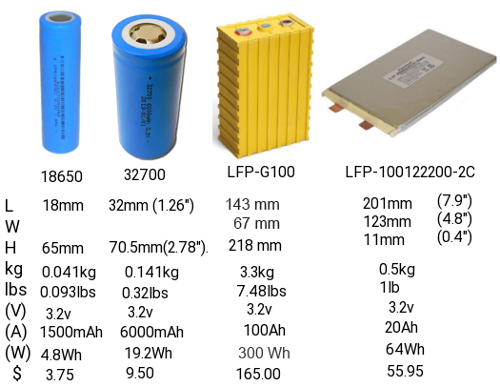

basic Gcell Types all being 48v for easy charging and compactness, we can do any size of vehicle. The smallest Gcell is 42Ah, followed by 84Ah and finally 144Ah. Where a 12v lead-acid battery is 85 lbs, the Lithium ones would be 34 lbs, 68 lbs and 105 lbs respectively. With 12v batteries at about 9”x7”x10” the Gcell▪s are 10”x10”x6”, 10”x10”x12” and 10”x30”x6”.

Using what I learned from the motohome conversion, If we have 3

basic Gcell Types all being 48v for easy charging and compactness, we can do any size of vehicle. The smallest Gcell is 42Ah, followed by 84Ah and finally 144Ah. Where a 12v lead-acid battery is 85 lbs, the Lithium ones would be 34 lbs, 68 lbs and 105 lbs respectively. With 12v batteries at about 9”x7”x10” the Gcell▪s are 10”x10”x6”, 10”x10”x12” and 10”x30”x6”.

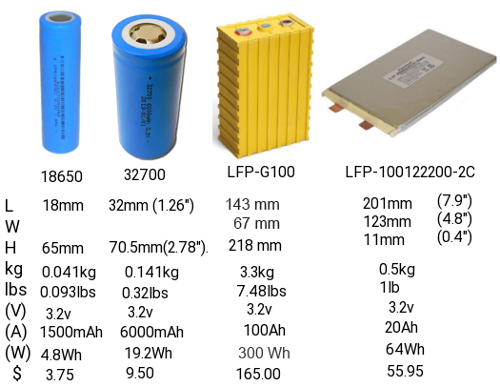

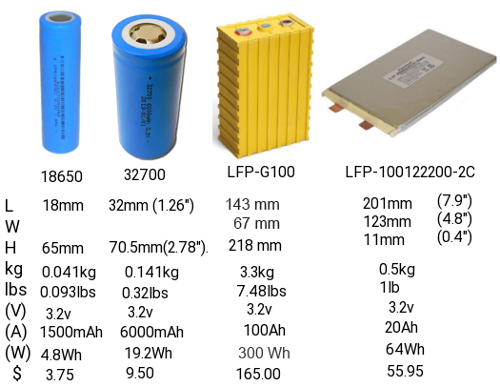

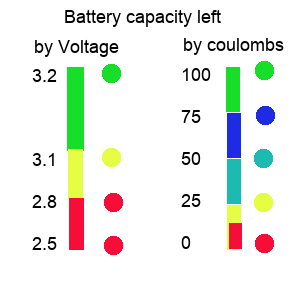

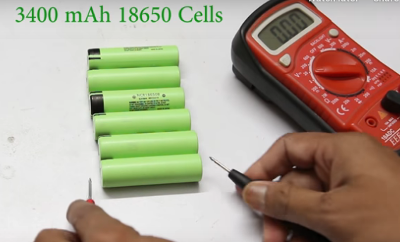

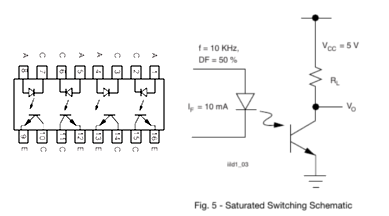

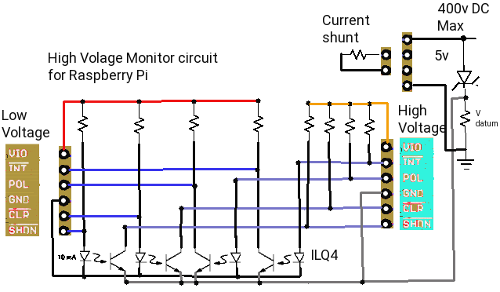

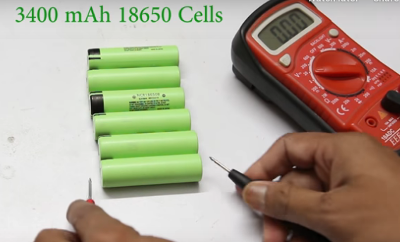

As seen to the left there are 4 basic types of battery make-up. The 32700 cell has 4 times the power of the 18650 at less than double the size. The LFP-G100 is made from 18650 cells in parallel but at 120 Gcells to make 384v is unreasonable. The fourth kind are very hard to source. So I chose 32700 made into Gcells like the LFP-G100 but instead of 3.2v@100A would be 48v@42A, 82A, 144A. We will be going into the batteries in depth later.

With our Gcell design we can access 12v for automotive systems by just providing a 12v tap on each 48v Gcell.

As for the analysis of battery types, the requirement per block becomes :

- 18650 ___ 48v 600A 6000cells $22,500 246Kg 27cm x 720cm x 6.5cm

- 32700 ___ 48v 600A 1500cells $14,250 211Kg 48cm x 320cm x 7.05cm

- LFP-G200 _48V 600A 45 cells $7,4250 218Kg 42.9cm x 100.5cm x 21.8cm

- LFP-100* _48v 600A 450cells $25,177 225Kg 20.1cm x 495cm x 220.1cm

So for the 32700 pack would be about 20" x 126" x 2.77". This gives us a rough working sizes to determine just how we will build the packs and their placement. The

analysis was from working on pack sizing to run a transit bus at 40,000 lbs fully loaded with passengers. A Mini-van is 1/10th the weight of a loaded transit bus which suggests 60A would be more than enough.

Weight distribution

The engine compartment reduces

weight by 675 lbs consisting of motor, torque converter and support systems for them. Then we added about 100 lbs for electric drive and inverter. In cockpit/dash we remove the instrument cluster and all the wiring for non-essentials and add the new digital dash computer. At the back we add the charge port, charger circuit and 733 lbs for 2 battery packs where we will remove the 178 lbs of fuel tank. After conversion we are more then 145 lbs heavier. We also plan to add solar panels to the roof too at about 280 lbs.

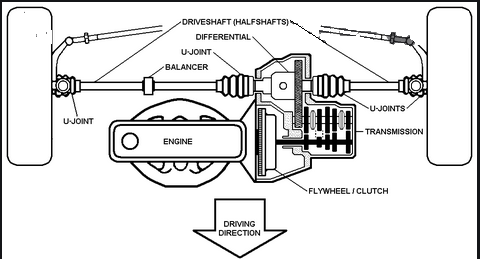

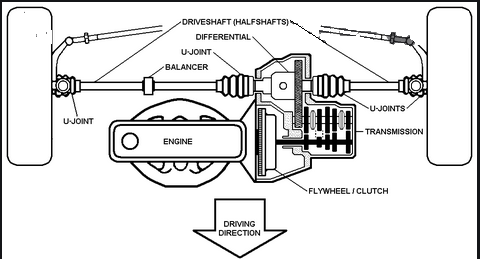

Chapter 05 EV Minivan : Drive Train

Drive train investigation

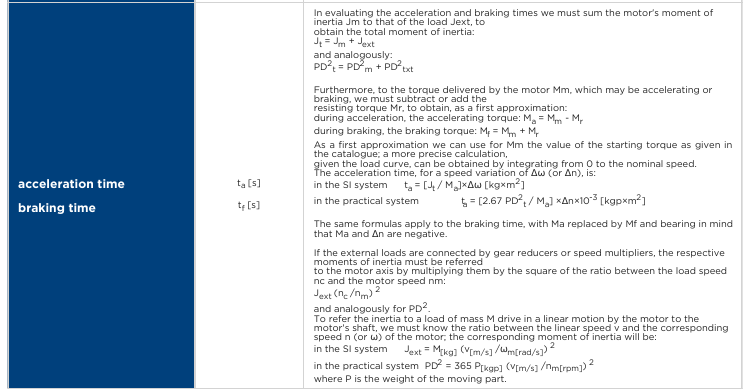

The end goal is to be able to move a 3400 lb mass on command. This relies upon the motor, gearbox, Inverter, and cooling technologies. We know that work creates heat. So if we expend energy to drive a motor fast,

it will heat up because it is under load. Supplying that energy is an Inverter that changes Battery power measured in DC to alternating power called AC. The inverter therefore also will be working hard.

Ultimately we want to move 2 tonnes (4000lbs) from 0 to 120kph (0 to 72mph) and we would

like to maintain this for 200kms (120miles). The laws of motion do not change just because we are driving the motion by a different method. So the distance traveled by the rotation of a 14" diameter tire will always be 3.14 (pi) x 14 (d) 43.96 inches until the tire wears down to it's minimum diameter of 13.21 inches which means it only travels 41.48 inches.

Mileage does not change either. There is 5280 feet in a mile and 12 inches to a foot. That's 63,360 inches to a mile. From this we can tell how many rotations of the tire are needed to cover the distance. (63,360

/ 43.96)= 1441.31 r/m. The differential uses a ratio of how many turns of the drive shaft it takes per rotation of the tire. We need to know this ratio as it will tell us how fast the gearbox output shaft must spin to make 1 rotation. Multiply that by the number of rotations per mile and we have the first part of the equation.

From the above we now can work out rotations needed to go a specific distance and then work out the maximum time we want to take to make that distance. So if our differential is 5:1 then we know the drive shaft spins 5 times to turn the wheel 1 turn and 5 x 1441.31 = gearbox turns to go 1 mile = 7206.55 r/m. Rotations are counted in rounds per minute (rpm). There are 60 minutes to an hour. So if we want to go 1 mile per hour, we need to divide 7206.55 by 60 minutes

to get the rpm. Which in this case is 120.1 rpm. To do the top speed of 72mph our gearbox will be rotating the driveshaft at 120.1 x 72 = 8647.86 rpm.

The preceding applies to a rear wheel drive but, and there is always a but, the mini-van is front wheel drive. It still has a differential but the differential is part of the transmission not connected to the

transmission using a drive shaft. With FWD our CV axles mate with the differential gear inside the transmission. The differential gear mates with an output gear on a secondary shaft. The secondary shaft has 2 to 4 clutch gears. A clutch gear when unpressurized free spins. Force hydraulic pressure into the clutch and the outer gear transfers rotation into the inner gear on the output shaft.

The preceding applies to a rear wheel drive but, and there is always a but, the mini-van is front wheel drive. It still has a differential but the differential is part of the transmission not connected to the

transmission using a drive shaft. With FWD our CV axles mate with the differential gear inside the transmission. The differential gear mates with an output gear on a secondary shaft. The secondary shaft has 2 to 4 clutch gears. A clutch gear when unpressurized free spins. Force hydraulic pressure into the clutch and the outer gear transfers rotation into the inner gear on the output shaft.

A series of solenoids are used to redirect hydraulic fluid to the appropriate clutch gear. Only 1 clutch engages at a time. All the clutch gear outer gears mate with different size gears on the main shaft. In this manor, when a specific clutch engages, it's outer gear transfers the new ratio to the secondary shaft. The Main shaft mates with a flywheel clutch gear that when presurized transfers rotation

from a torque converter to the main shaft. The torque converter mates with the engine output shaft. Part of the torque converter and Flywheel clutch has a hydraulic fluid pump that is used to pump the hydraulic fluid to the necessary components.

At top speed of 66mph, driveshaft

rpm is 2907.5rpm. At local highway speeds here of 100kph to 110kph (60mph to 66mph) we need a motor that can sustain an rpm of 3000. Most motors run 500 to 3500rpm as upper limits with 1500 being a go to standard. This would mean we need a gear ratio of our gearbox to be 6:1 @ 500rpm and 2:1 @ 1500rpm and 1:1 @ 3000rpm. But from the source "electric cars are for girls" they say Most AC electric motors run 230v AC @ 60 Hz and a top speed of 1750rpm. They also say that to create 230V AC from a DC source you need 340V DC from your Battery pack. Not to be thrown some curve, it's time to do more investigation. I tried to find some concrete facts about motors, torque, and weight classes they can safely handle but none could be found. So time for different approach we will review TV programs from "Jay Leno's Garage and web cast from EV west to try and get more info.

Jay Leno's Garage did 2 EV Bus Episodes. One was for Econoliner in California and the other was a repurposed Transit bus. Both busses were about 18000 lbs without passengers and 38000 lbs when full of passengers. In comparison to my first project (an EV Motorhome), My fully loaded motorhome comes in at 17,500 lbs and 24,500 when towing a car behind it. My Motorhome is therefore lighter. The Busses have a kwh/m of 1.8 to 3.8 depending on load, where my Motorhome is 1.75 to 2.4 depending on load, and a mini-van

is 0.34. Both busses use more than 360v @600 Amps = 234Kw and where the repurposed bus provides that it can travel at highway speeds of 50mph for 100 miles to a charge, the Econoliner travels in the city with many start stops at an average speed of 9mph over an 18mile route with fast recharge enroute and runs 24 hours a day. The values for the repurposed bus suggest it is making the trip at far less than full since they have 234kw and to do 100 miles would take 380kw if full of passengers. In the episodes, they mention HP is about 170 to 200 and that the real killer is torque. Because electric motors have instantanious torque it tends to destroy conventional transmissions based upon multiple gear ratios so EV's are better off with fixed gear styles. And lastly that an expected decrease of brake wear of 50% was remarkably exceeded such that brakes should last > 500,000 miles over the ICE at 20,000 miles.

The EV-West podcast basically itemized how a DC electric motor is much larger than an AC motor of the same drive potential. While DC motors are plentiful and cheaper, both in cost of the motor and in cost to control them, they have serious limitations. Firstly, the maximum vehicle weight of 3000 lbs from a single motor and ganging two motors

to increase load capabilities is counter productive. The motor weight itself is heavier than an AC motor. Two DC motors is 1 & 2/3rds heavier than an AC motor and typically 30" long compared to an AC motor that is 15" to 18" long. DC motors run much hotter then their AC counterpart. Heat is so high that long distance at higher speeds is almost impossible without a custom transmission.

Ok so here is what I learned from this:

- DC motors won't work they have to be AC drive

- Weight/10000 = kwh/mile

- Interior amenities are run from regular batteries and recharged by an inverter.

- HP is between 170 and 200, Torque at about 1200 ft-lbs

- 50 mph. is not a problem and with the right gearing 66mph is doable

- With regen braking brakes may last 25 times longer than on ICE

- A small 15" x 20" electric AC motor drives the axles through a gear box connected to the differential. The motor is run by an inverter and controller.

- braking is regenerative

- They may have 1 battery pack for a total of ~360 volts. That means the battery pack need to add up to 360+v and lithium ion cells which they are also using are 3.2v each. That means 1 pack contain a minimum of 113 cells in series. Then they have 230.4 kWh in the spec. v x A = w so 230400 / 384 must equal the A rating. Which is

600A. So this bus is probably using 462 cells in parallel if using

18650 cells for a total of 55,440 cells.

In chapter 12 we will go into depth on the batteries. We will cover types of battery and the effect on quantity, organized grouping, Pack Voltages, Current, Wattage and a number of other factors.

On the bright side it does confirm what"electric cars are for girls"said about AC motors needing over 340v DC to get 230v AC for the

motor. Both bus conversions talking about ~360v in Battery power. With high voltage source and stepping it down by 1.669 to get 230v AC, the current demanded by the AC motor is 1.669 less at the source. As a result, An AC motor demanding 10A @ 230v means the source actually only needs supply 5.99A. This is the run current. At start, the first 1/60th of a second (based upon 60Hz) has surge current about 25 times higher for that 1/2 second. So our 10A motor can be expected to draw 250A for 1/2 second then as the rotor of the motor begins to turn the current drops over the next 6.5 seconds to under 60A then in full rotation settles at the 10A. This of course assumes

the motor is being told to run at maximum rotational speed. What happens at the motor is reflected equally at the source. The source will see 150A surge for 1/60th of a second then 6.5 seconds of 36A and then the run current of 6A. This is similar to what happens on an ICE when the starter engages. The ICE Battery has a rating of 800 to 1500 cold cranking amps. As you turn the key to start the battery must supply 800Amps plus thru a 2/0 cable to the starter and 60 to 80 amps to the spark plugs. Once the engine is running, an alternator recharges the battery. If the alternator fails or the belt breaks, the battery supplies the 60 to 80 amps until the 85Ah battery is depleted. Then everything stops.

So moving on...

The Drive Inverter sits up front with the motor so it's three 2 gauge cables can adequately supply the motor. Under the chassis to the back we have a lighter 4 gauge cable to the charge port and batteries. The

cables are overkill as far as run current goes. They are specific to handle the surge currents.

Our Mini-Van conversion replaces the 390 lbs engine with a 90 lbs motor & inverter. The front wheel drive transmission is kept but modified.

The fuel tank is only 18 lbs empty and 138 lbs full. The batteries are going to take 585 lbs at least. Under full occupancy, passengers and cargo are qualified at 1000 lbs to meet the GVWR of 4400 lbs. So up front we have 300 lbs lighter and at the back we are 300 lbs heavier. Again we want solar charging which might add as much as 250 lbs. The GVWR of a motorhome takes into account 2 occupants but the Curb weight excludes occupants on passenger vehicles. So we also must adjust our battery needs from 0.34kwh/m to 0.44kwh/m. To compensate for the heavier weight of passengers. The pack weight changes from 585 to 733 lbs. The pack is now 120 x 20 = 2400 cells. The cost has risen to $22,800.

The cells are a difficult concept because it refers both to a cell being a tiny cylindrical AA type battery and also to the groups of them

forming the whole. A prismatic cell is made from 100's of individual AA type looking batteries also called cells.

Motors

Three types of motor for EV's. We have the old low voltage type DC motor, The newer tech AC 3 phase, and the OEM AC 3 phase. All three can move the mini-van but each has it's own set of problems.

DC Motor

Typically run from 12v lead acid cells, it is abundantly available, low in terms of cost, and great low end torque. At higher speeds, it has virtually no acceleration. It works fine at low speed short distances but can overheat easily under heavy load, higher speeds, or long distances. The controller is simple and regulates the speed only.There is no regenerative braking (free wheels) and needs a transmission to accomplish speed range and reverse features. Heavier motors

Typically run from 12v lead acid cells, it is abundantly available, low in terms of cost, and great low end torque. At higher speeds, it has virtually no acceleration. It works fine at low speed short distances but can overheat easily under heavy load, higher speeds, or long distances. The controller is simple and regulates the speed only.There is no regenerative braking (free wheels) and needs a transmission to accomplish speed range and reverse features. Heavier motors

AC 3 phase Motor

The go to solution for most EV conversions. Can attain higher speeds from higher voltages, Single gear ratio can do full range of motion with forward and reverse. handles higher loads with higher current packs, not near as bad heat generation, A more complex controller handles the speed and direction. Top end torque and passing power can be compensated for by the controller through a combination of voltage, frequency, and current. Motors are far lighter and smaller. Regenerative braking is possible. Few suppliers and larger costs.

The go to solution for most EV conversions. Can attain higher speeds from higher voltages, Single gear ratio can do full range of motion with forward and reverse. handles higher loads with higher current packs, not near as bad heat generation, A more complex controller handles the speed and direction. Top end torque and passing power can be compensated for by the controller through a combination of voltage, frequency, and current. Motors are far lighter and smaller. Regenerative braking is possible. Few suppliers and larger costs.

AC 3 phase OEM Motor

Hard to find except salvaged from wrecks, these are the goto for people that want to incorporate a custom solution into a similarly sized conversion. That is to say if you want to put a motor into a 3000 lb vehicle of roughly the same style as the motor from a wreck of a 3000 lb vehicle you can probably do it. The motors will be high voltage, high current, water or oil cooled, and have a special controller/inverter that checks, rotation, current draw, temperature, and other dynamics.

Hard to find except salvaged from wrecks, these are the goto for people that want to incorporate a custom solution into a similarly sized conversion. That is to say if you want to put a motor into a 3000 lb vehicle of roughly the same style as the motor from a wreck of a 3000 lb vehicle you can probably do it. The motors will be high voltage, high current, water or oil cooled, and have a special controller/inverter that checks, rotation, current draw, temperature, and other dynamics.

The one underlying thing that is emerging is that unlike ICE cars where demand for their engines is low, demand for the fuel left in the tank is non-existent, the electrics have high demand for motors, controllers, and Battery packs. This is because 1) they all are expensive, and 2) they last for years even decades. Being virtually a

maintenance free system is quite different than their ICE counterpart which has thousands of moving wear prone parts.

The selection process

Many factors come into play in this process. Most focus on Speed, Acceleration, Distance, Charging, but those come after the computational work is done. For the motor, there are the factors of which type, how much voltage does it need, what is it's operational range (how many continuous rpms), how much current will it demand, what kind of load can it handle and for how long.

Then we have the drive coupling which can be gearbox, direct drive, transmission , and the coupling of the motor to the rear differential either directly or through a transmission/gearbox.

All this then has to be managed by the controller which must match the motor gearbox combo, and has certain demands it places on the required energy source (batteries).

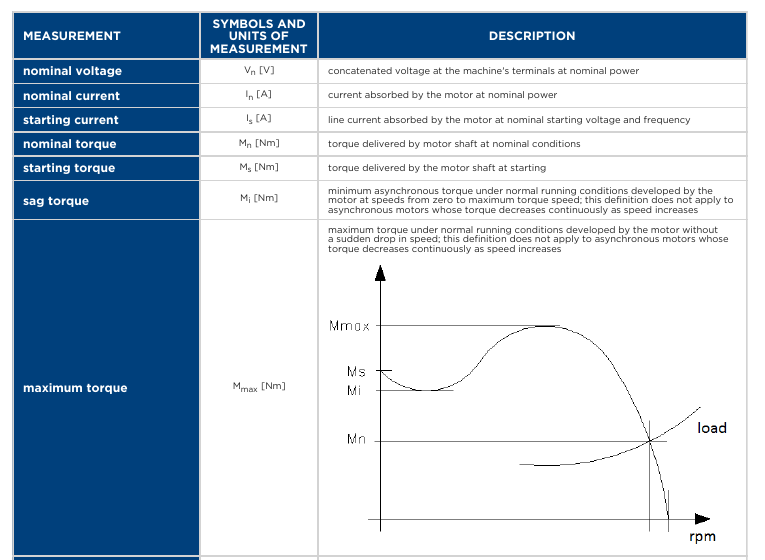

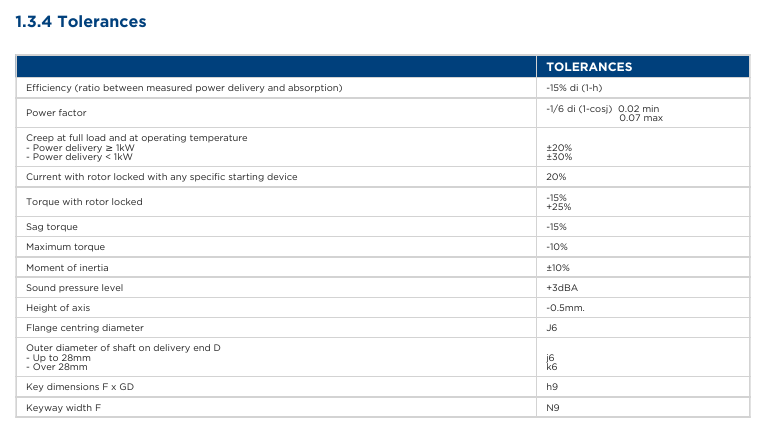

Motor Starting Currents

Typically, during the initial half cycle, the inrush

current is often higher than 25 times the normal full load current. After the first half-cycle the motor begins to rotate and the starting current subsides to 4 to 8 times the normal current for several seconds.

How do you calculate the maximum current of a motor?

https://goodcalculators.com/motor-fla-calculator/

Motor Full Load Amperage Calculator

Number of Phases: 3

Motor Rated Voltage: V 230v

Motor Rating: 5 hp

Motor Power Factor: 0.91

Motor Efficiency: 85%

Results

Three Phase Motor Full Load Amperage (FLA): 11.96 A

Number of Phases: 3

Motor Rated Voltage: V 230v

Motor Rating: 4 kw

Motor Power Factor: 0.91

Motor Efficiency: 85%

Results

Three Phase Motor Full Load Amperage (FLA): 11.03 A

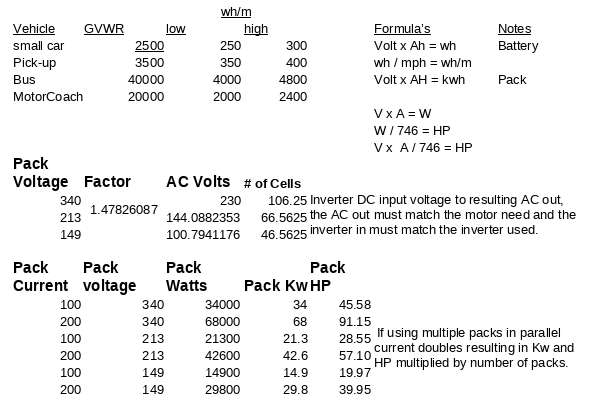

As the label suggests, wh/m is how many watts of power it takes to move a mile at a given speed.

If you use 250 wh/m @ 20mph = 250*20 = 5000w but if you use 250 wh/m @ 50mph = 250*50 = 12500w. They are both right. This is because at 20mph the motor does less work than at 50 mph.

So our 4000 lb Mini-van is going to require 400wh/m. But I picked something else from that video. The lecturer also made a point that it isn't just vehicle and contents but it also includes air drag, rolling resistance, and towed trailers.

An Inverter takes an Input voltage and converts that to AC 3 phase voltage. The motor you wish to drive from the inverter has to match the inverter output so to drive a 144v motor you need an inverter with 144v AC output. Likewise, a 230v AC motor requires an inverter with 230v AC output. This limits choices since Battery pack voltage = Inverter input DC and Inverter output AC = Motor voltage.

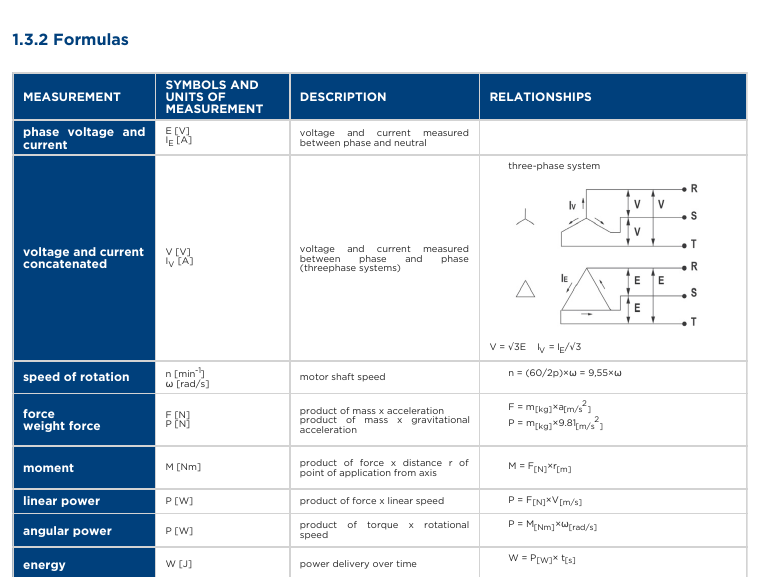

AC Induction motor basics:

Ac motors are the most common motor used in applications because they are AC and readily available. They run quietly and run a very long time and are economical.

All AC motors have same basic components:

1. A stator

2. A rotor.

The stator is the stationary coil that creates the magnetic field. This field reacts with the rotor bar to produce rotation. In 3 Phase, the stator sets

up a current and a magnetic field. The magnetic field causes a

rotation due to the 120 degree Phase offset. The current induced in the rotor sets up it's own magnetic field.

An important thing to remember about 3 Phase is they are offset 120 degrees apart and are self starting.

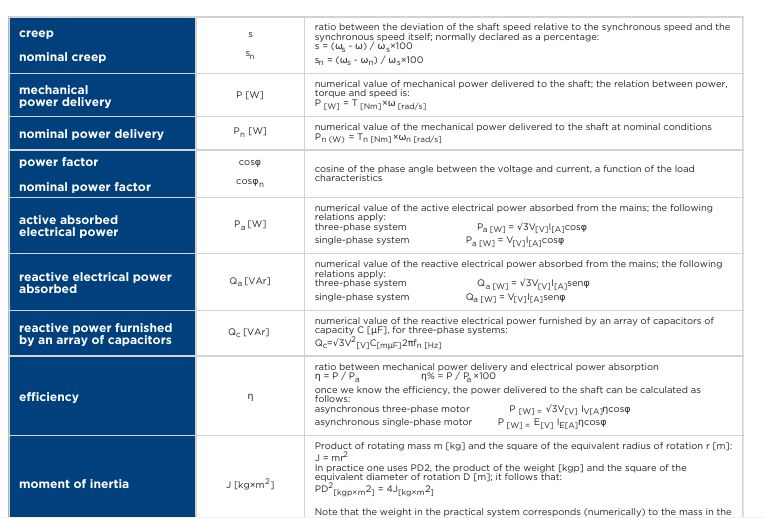

Slip: Slip is the difference between synchronous speed and actual speed of the

motor. Induction motors rely on the slip to induce current in the rotor and the amount of slip changes as the load on the motor changes.

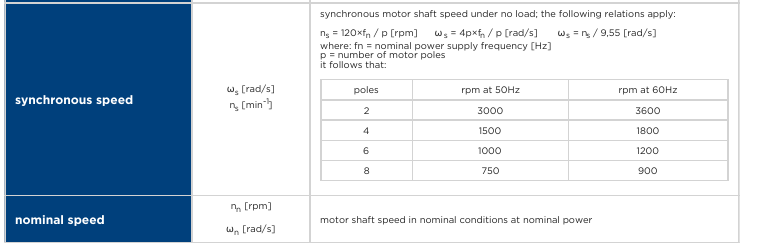

In order to change the

speed of an induction motor the frequency must be changed. This is accomplished with a motor control and the most common is a variable frequency drive or VFD. Without a VFD the motor speed is fixed by the equation 120 * Frequency / number of poles.

120 * 60Hz/2 = 3600rpm

120 * 60Hz/4 = 1800rpm

120 * 10Hz/2 = 600rpm

120 * 200Hz/2 = 12000rpm

So as we see here, the VFD control part of the inverter varies the frequency. In the first two examples there is no variance. so the motor always runs

at full speed which is governed solely by the number of poles. Not what we want for an EV because we want to adjust the speed based upon the accelerator pedal.

So in the next two examples our accelerator pedal starts off at 0 and the motor is 120*0/2 = 0rpm. Then we push the accelerator down a bit and get 10Hz which spins the motor at 600rpm and we move. Then we push the

pedal to the floor and the motor gets 200hz and the vehicle takes off like a rocket.

Two things things to consider is running speed and starting torque.

1. Running speed: this is determined by power supply frequency , the number of poles and the slip of the motor due to load. The specs will show the torque of the motor.

2. The starting torque is the chief limitation of the AC motor. If the motor must start with a load on consult the motor

manufacturer.

Compared to single Phase motors the 3 Phase motor has a higher power density, greater starting torque, and more efficient than the single phase motors. They start on their own.

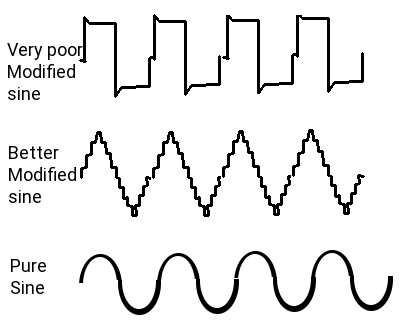

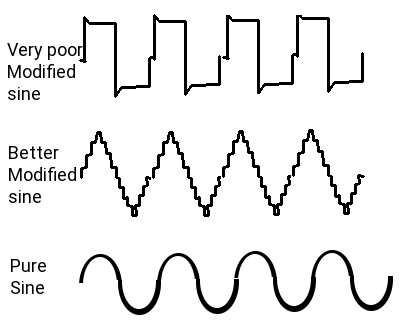

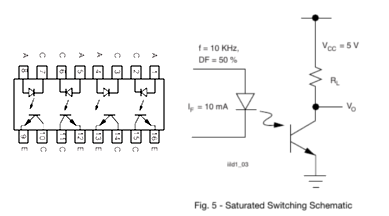

Lets add another cog in the design. We can have Modified sine wave inverter controller or we can pure sine wave inverter controller. The Modified Sine wave is cheap and does a poor job as it creates a shakey sine wave made up of almost square waves. These cause a lot of noise

interferance effecting everything around. The pure sine wave (like you have in your house 120v AC lines) is a clean smooth sine wave with very little to no ripple. Pure sine wave inversion is far more expensive. Where the cheap inverter may be $30 to $90 the pure sine wave ones may be $350 to $19000. Also, the cheap one will damage any form of digital electronics like Laptops, clocks, radios, TV, and the noise harmonics can interfere with medical equipment even pace-makers!

Lets add another cog in the design. We can have Modified sine wave inverter controller or we can pure sine wave inverter controller. The Modified Sine wave is cheap and does a poor job as it creates a shakey sine wave made up of almost square waves. These cause a lot of noise

interferance effecting everything around. The pure sine wave (like you have in your house 120v AC lines) is a clean smooth sine wave with very little to no ripple. Pure sine wave inversion is far more expensive. Where the cheap inverter may be $30 to $90 the pure sine wave ones may be $350 to $19000. Also, the cheap one will damage any form of digital electronics like Laptops, clocks, radios, TV, and the noise harmonics can interfere with medical equipment even pace-makers!

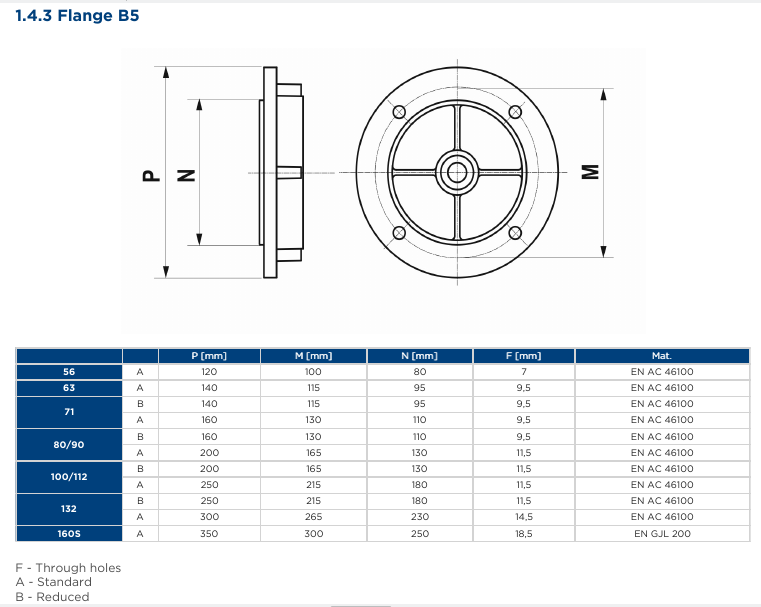

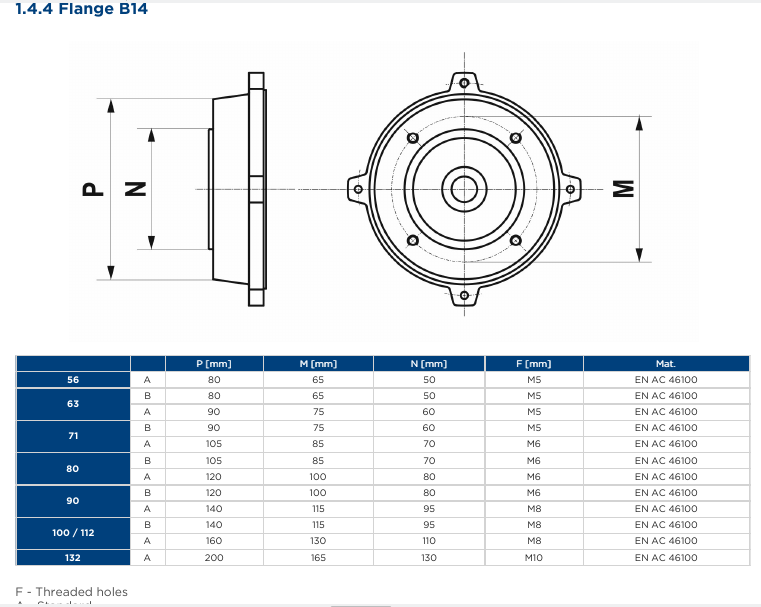

As a general rule you select the battery voltage and amperage first, then select the motor that provides the drive range potential and adjust the battery packs to meet the motor needs. Then look for an inverter or build an inverter that satisfies the source input to the required output. We have the Battery plan at 384v DC @ 168A and have found siemens and motovario that supplies 230/400 motors in a large assortment of abilities. The 230/400 rating in general says it runs from 230v AC or from up to 400v DC under PWM

or VFD or both.

The Siemens GP 1LE10 IEC-LV-Motor 1E2 seems to be a good match with rpms from 50rpm to 5000rpm. When you get to chapter 12 you will note that when they state the current draw it is based on initial instantaneous current at point of acceleration and

not the run current. If the current was the run current maximum

vehicle range at 46KW would be less than 2 miles. and we know that if we use 0.44 KWh/m which at 60mph would be 26.4kw in that hour. Current draw would not be 119A = < 2m range but in fact would be 5.98A

I told you this is a big topic or maybe I'm just wordy. We still have yet cover working with HP, Torque values, drag co-efficient, Kwh, Inverters, Charging systems, Distribution systems, Cockpit control and dash display systems, and ways to replicate electrically what was done using the ICE and it's mechanical systems. Then we can move on to actually doing the conversion.

Chapter 06 EV Inverters and controllers

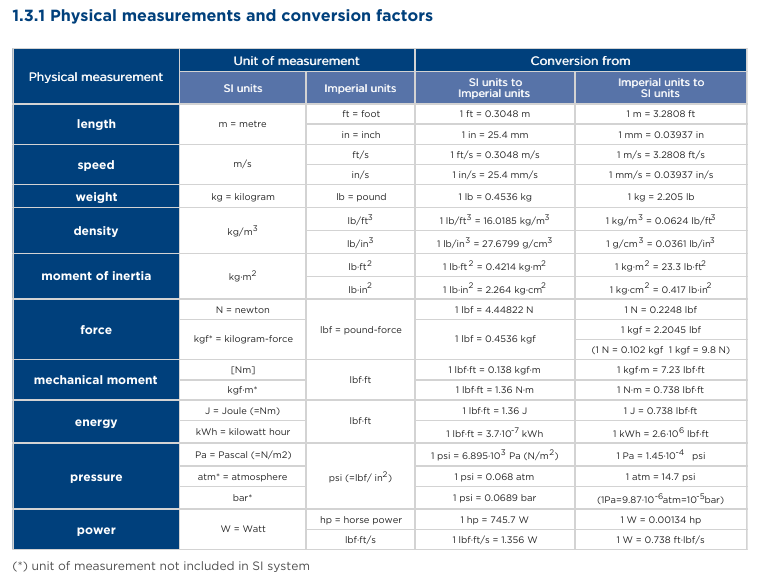

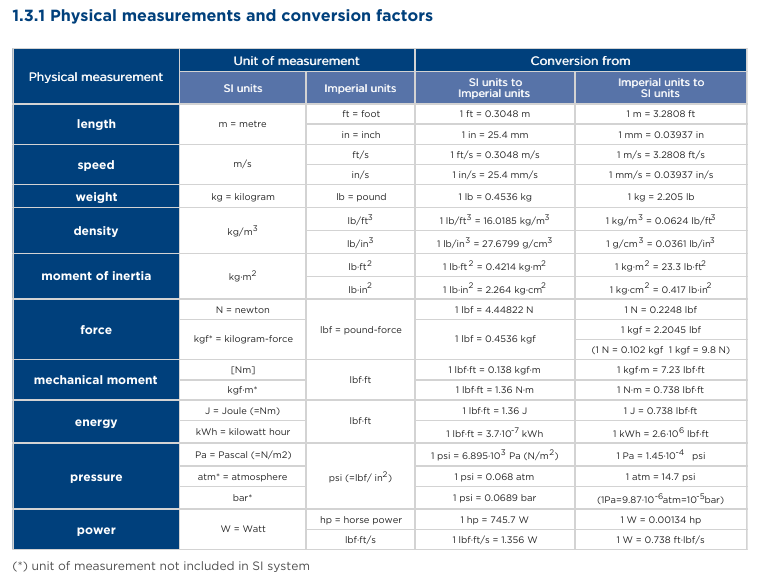

Torque vs Kw

- Torque (lb.in) = 63,025 x Power (HP) / Speed (RPM)

- Power (HP) = Torque (lb.in) x Speed (RPM) / 63,025

- Torque (N.m) = 9.5488 x Power (kW) / Speed (RPM)

- Power (kW) = Torque (N.m) x Speed (RPM) / 9.5488

- Torque ft-lb = NM * 0.73756

- Torque NM = 8.86 * in-lb

Inverters

These are work horses of the electric vehicle. The motor inverters job is to convert the supplied power from the batteries to the motor in the

correct voltage, current, and frequency to drive the motor at a

specific speed of rotation. The house inverters job is to convert the supplied power into pure sine wave 60Hz at the correct current for the coach living area on a motor home. A mini-van however does not need a house inverter.

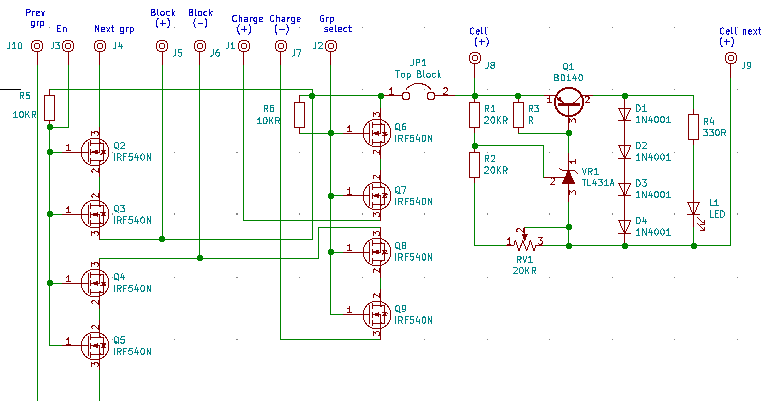

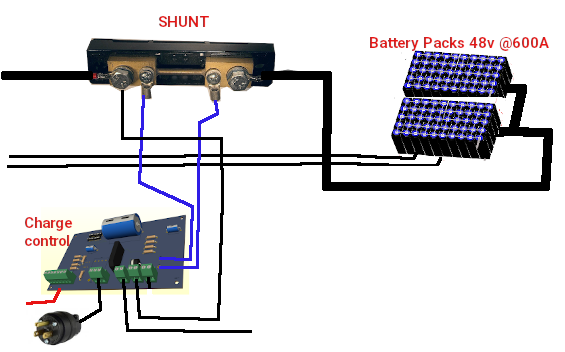

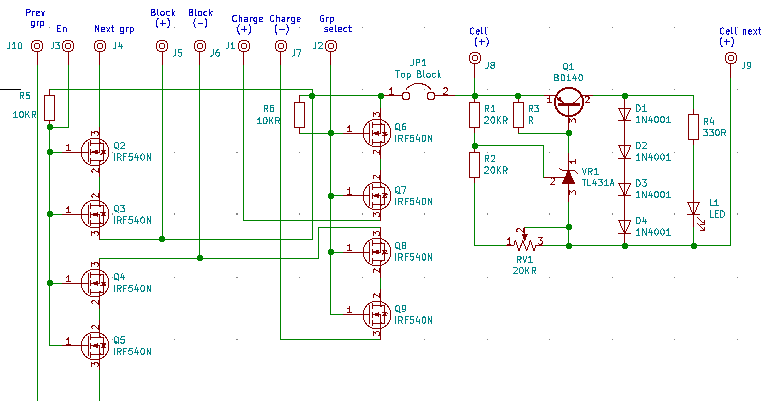

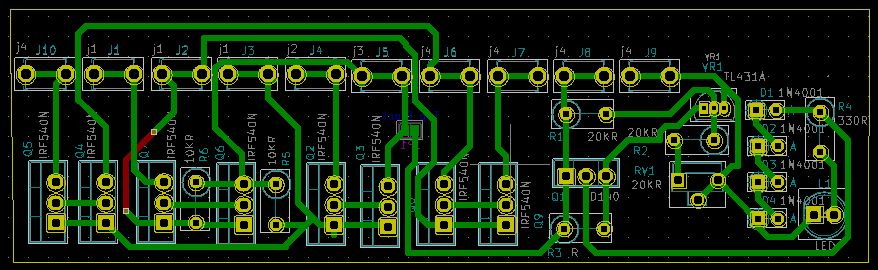

On the driveline side of things, we have Battery condition monitoring and real time Battery capacity control, with voltage taps for 12.8v, 48v to run the needed systems. The traction motor, runs from direct inversion of 384v using VFD and PWM..

Inverter/Converter Tandem Units

An inverter/converter is, as the name implies, one single unit that houses both an inverter and a converter. These are the devices that are used by EVs to manage their electric drive systems. Along with a built-in charge controller, the inverter/converter supplies current to the battery pack for recharging during regenerative braking, and it also provides electricity to the motor/generator for vehicle propulsion. EVs use relatively low-voltage DC batteries (about 210 volts) to keep the physical size down, but they also generally use highly efficient high voltage (about 650 volts) AC motor/generators. The inverter/converter unit choreographs how these divergent voltages and current types work together.

Because of the use of transformers and semiconductors (and the accompanying resistance encountered), enormous amounts of heat are emitted by these devices. Adequate cooling and ventilation are paramount to keeping the components operational. For this reason, inverter/converter installations in vehicles have their own dedicated cooling systems, complete with pumps and radiators.

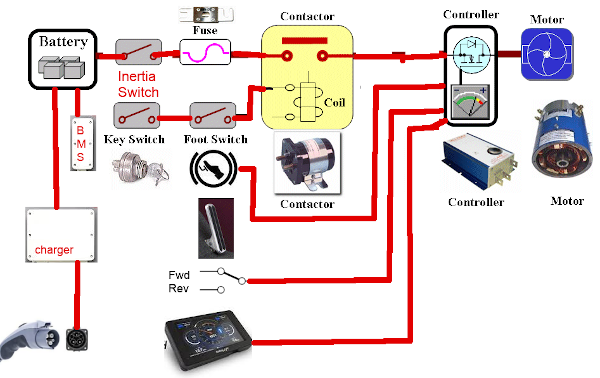

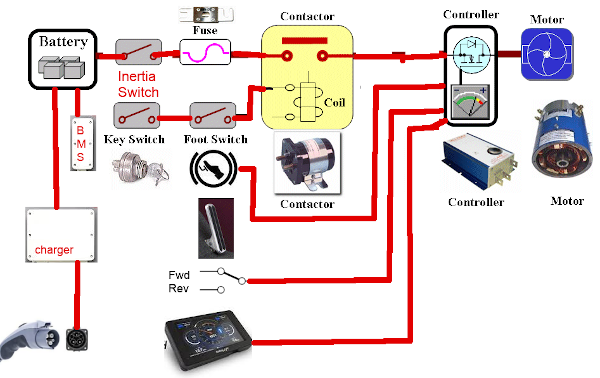

The basic EV

The diagram here is over simplified. It works as a working model for operation of an EV. If you used this model, yes you would have electric drive but at full speed all the time and once you are out of power everything stops. So we need to enhance the drawing.

The diagram here is over simplified. It works as a working model for operation of an EV. If you used this model, yes you would have electric drive but at full speed all the time and once you are out of power everything stops. So we need to enhance the drawing.

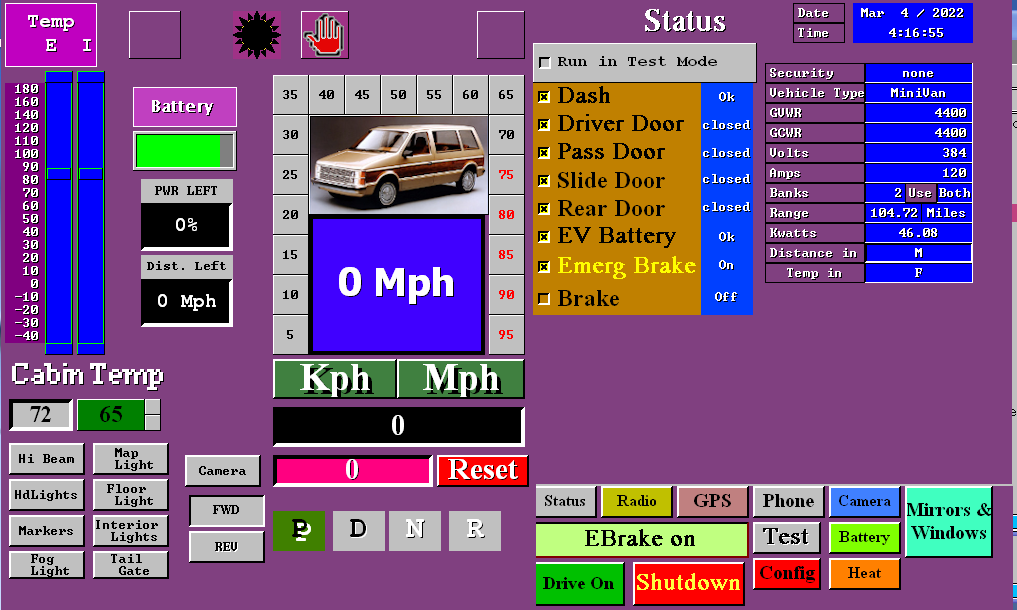

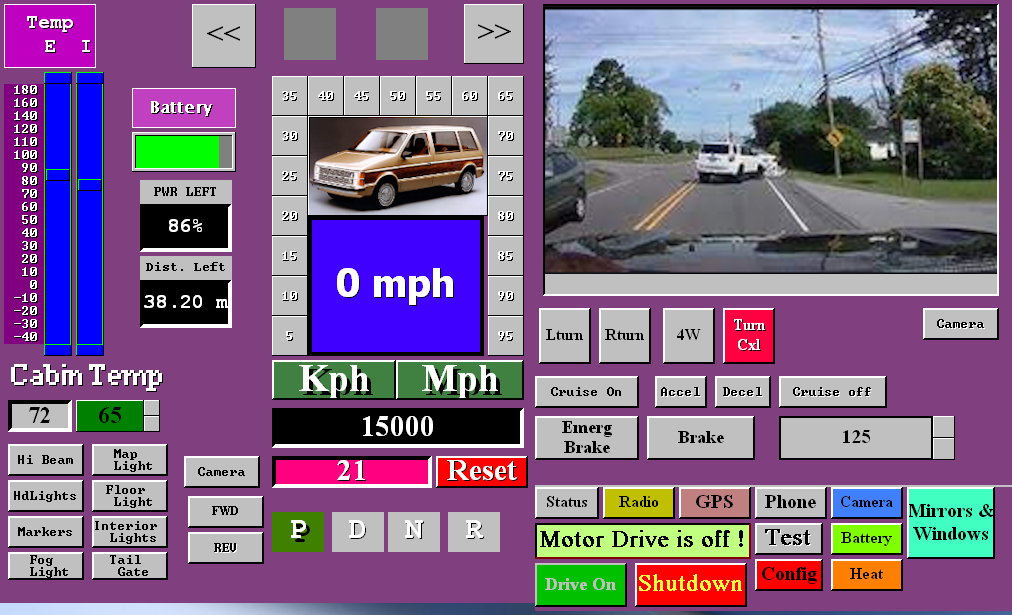

You notice it is basically the same with the missing components now shown. The Inertia Switch stops everything in the event of an accident, The BMS protects the batteries from over charge and over draw, The recharger and port to restore the batteries, Accelerator part of the pedal to regulate speed, the dash to monitor speed and results, and the forward and reverse switch to choose direction of travel.

Additional to these systems, are the automotive systems for lights, braking, a/c, radio, cooling and steering. All of which are not shown on this depiction.

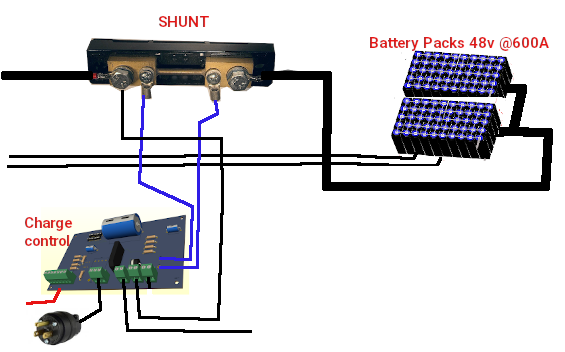

Ideally there should be cutoff switches between the battery banks

The contactor

This a

High voltage High current solenoid. It is controlled through a low voltage side operated by the key switch/foot switch. When you press slightly on the accelerator, the switch engages and if the

key is on, power flows to the controller through the contactor.

Inertia switch

Is a high current high voltage device that cuts power under abrupt impact.

It must be reset for power to resume.

Main Fuse

Has to be rated for the maximum Voltage and current and is designed to blow

if limits are exceeded.

Key Switch

Is the master on/off of the car.

Foot Switch Accelerator

Your dynamic speed control. The switch part enables the contactor to supply power and the Accelerator part says how much power to supply.

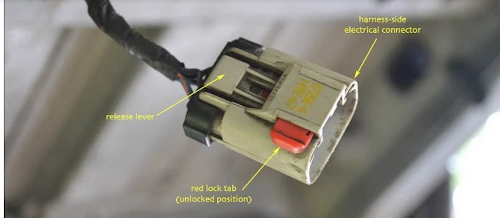

The Charge Port

This has both the supply lines to the charger a interlock switch to tell the charger external charge is securely attached. It is possible for there to be 2 or three charge connections depending upon design. You could have 230V AC @50A, 120 @ 30A AC, 115v @ 15A AC even some like 460V 600A.

|

Dash Display

Of coarse you want a fancy dash display that tells you how much charge you

have, estimated distance left, Pack condition, Speed and for the hot rod types, your rpm/1000. That last item is no longer required as you aren't needing to know at what rev you need to shift.

Manual transmissions are not found anymore in main stream life and EV's don't even have one most of the time.

Controller

Ah! the heart and brains of this outfit. The controller also known as the Inverter, after the function that it does. In the realm of DC motors these do not exist. But for AC motors they are the most necessary part. Types

range from the very trivial control to highly sophisticated ones. Basically, they take an input voltage range to produce an AC output range of voltage. Voltage controls the speed, well kinda.

In a flat inverter it controls the speed, but in a structured inverter, changing the output frequency can also be used to increase the speed. Current from the pack of batteries provides the torque drive.

Depending on the motor chosen for a given project, it may already come with a matching controller. You can use the supplied controller if one is given, or can also design and build your own. Most OEM's build

their own to their exacting specifications. But the design of such is a monumental task involving IGBT's to control high voltages and currents, fast switching and sensing devices and the like.

|

|

BMS

Essential to the health of the batteries is the Batteries Management System. It's job is to identify cells that are not as charged as others and balance things. It looks at temperature, State of charge, amount of charge or discharge in an effort to keep all cells in prime condition.

Charger

There are a wide range chargers and

charger designs. The charger must optimize the input power (AC) into (DC) known as rectifying it. Then charging the batteries from this rectified output. A good charging system will not allow the batteries to be over charged and will in fact shut off when they reach full charge. With Lithium Phosphate, you can not drain them more than 80% and can not charge more than 95%. To do so would damage the cells. Also take care considering fast charging. Charging at 4.2v per cell

is typical of BMS monitored and controlled systems but, and there is always a but, 4.2v will degrade the cells life. A smart choice is to charge at a maximum of 4v which can extend a cells life by more than 25%. Current actually does the charging. If cells are rated for 1A or 6A for example they should not ever be charged faster than that. This is known as the batteries 1C rating. fast charging charges at 2C, 3C, 4C. Some liFePo4 cells can tolerate 2C but not all. Even fewer can

tolerate 3C and none can tolerate 4C.

So consider this, you have a Pack that is 8 Gcells in series so you have 384v and your pack current is 600A and you are going to charge from an AC home outlet. So you have 120v @ 15A. You have an ideal Inverter charger that is very efficient and @ 384v has 5A for charging. This will do great and charge the pack over the next 5 days. Each cell is

happy because it gets 0.2 amps slow charge. But you get to a fast charge station 480v 300A fast charge and give it a wirl. The on board inverter converts 480v to 384v and gives it to the batteries. The battery packs are very angry with you. If the individual cells are 18650 they can handle 1 maybe 1.5A if they are 1.1A cells you are charging at 3C. if they 1.5A cells you are at 2C. If they are 32700 cells they are ok because they can deal with 6A.

The PWM Pure Sine Drive Inverter

The Pure sine wave inversion on the surface does a clean AC wave output to the motor. It gets it's cue from the Accelerator Potbox as to what the demanded speed of rotation is to be. It then needs to read the direction switch (FWD/REV) and use this to determine the frequency to deliver to the AC motor. IF 60Hz is the full on normal run speed of the motor at say 3500rpm, and you are asking for 200rpm then the pulse given to the motor 17% of 60 cycle per second. if I did the math right the pulse would have been .17 seconds.

Chapter 07 EV Minivan Theory wrap up

Thus far we have examined the reason for going the EV Minivan route. I have concluded that even though I will be sinking $22,000 into a Minivan that is 40 years old it is a wise investment. You buy a new Minivan and drive it off the lot and loose 30% of it's value right off. After a few years you are lucky if you get 10% of what you paid for it. During your ownership you will have paid for your lifestyle with hard cash for fuel, oil changes, typical ICE failure problems that amount to major mechanical bills, tows, and expensive parts. In the end you spend roughly $30,000 for

the vehicle, upwards of $4000 a year for upkeep, another $2000 to $6000 a year for traveling, and if you hang on to it for 5 years that's in excess of $60,000 and you might get $5,000 trade in. In the end you are out of pocket $60,000 for 5 years (12,000 a year). Your next 5 years you can expect the same. And little old me had an old unit, and based upon my research spent $22,000 for conversion, spent another $500 to $1000 a year for operation if I was unlucky and was charged for power. So my first 5 years cost me $28,000 and instead of trading in I go the next 5 years for $5000. Being frugal, I put away money in the bank as if I was running a gas hog and have $20,000 that

I can use to at the end of the second 5 years to replace the

batteries that need replacing. Our yearly cost of ownership averaged over 10 years is $2,500 and the vehicle owes me nothing and I am debt free. You on the other hand have payments on another 30,000 plus a yearly cost of 6,000 or so.

We examined the chassis and discovered we can remove 490 lbs from the old ICE system. We have now got roughly 8 cu ft of space for our EV Batteries. But have a constraint on how much weight we can add in batteries. In speaking of the batteries we have 4 basic types of battery topography that we can use. Three of the 4 topographies allow

us to match and control quality of components for the highest in use life. Removing the complexity of the ICE has reduced us to having a maintenance free motor good for 1 million or more miles, a traction drive inverter, a cockpit control system and 2 Banks of batteries for which we know each and every part of the system. If a cell dies we are left with a still running vehicle but the ICE owner can have thousands of possible failure causes in his system. Check engine light doesn't tell you much does it?

Looking into our drive train we discovered that our unit is 1/8th the weight of a Motorhome and smaller in size. The Kwh/m was determined at 1/10th the GVCW and total KW = V*A, Electric HP is much less in requirements than an ICE needs and if we prevent shortened battery life by charging at too high a voltage or current we can extend our

batteries useful life.

We dove into the basic theory of AC motors and outlined how AC motors work and why they are a good choice. How to use them in a variable speed set-up rather than to just full on drive to their maximum and keep them there.

Finally, we discussed the inverters and converters that we will be needing and

constraints we need when talking about the different purposes. How using a single 384v battery source can satisfy providing for 12v systems, 5v systems, High voltage systems for drive

operation.

I think we are now ready to go to the next step and define the systems for real.

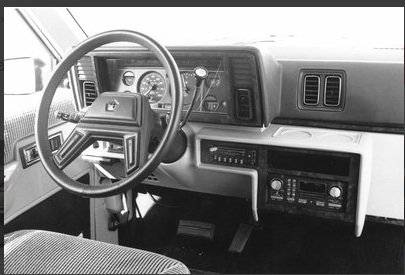

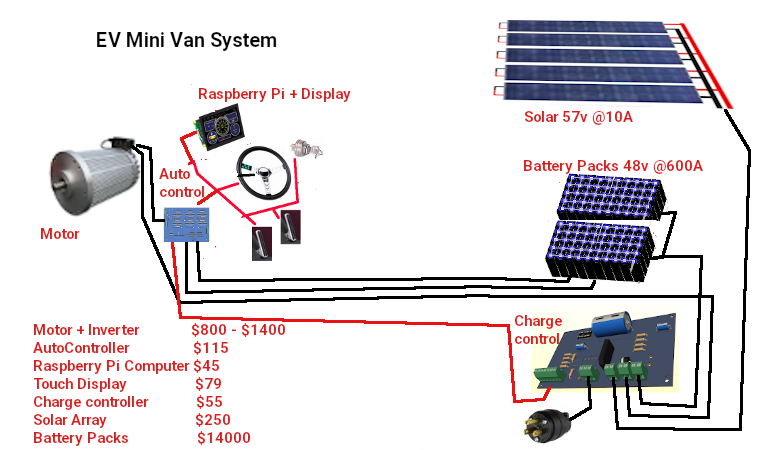

Chapter 08 EV Minivan Basic System

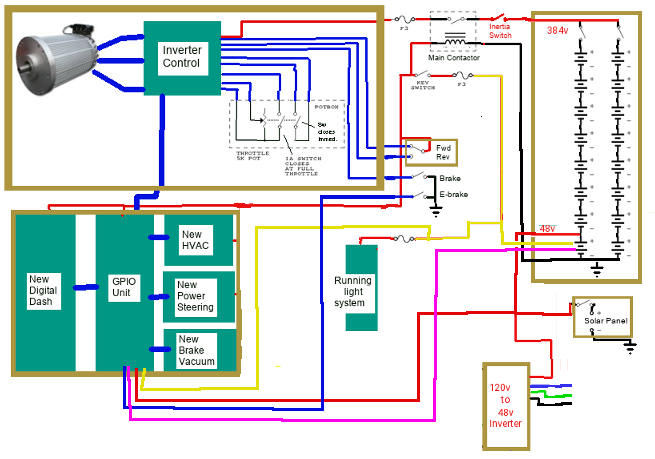

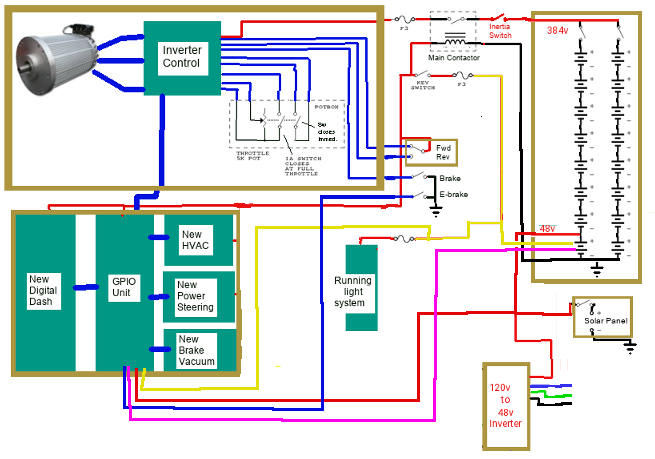

The Minivan will retain almost none of the electrical systems it once had. We will keep the wiring to the lights but install new lower powered LED lights. Keep the fuse box but repurpose it. Keep the stearing column and all it's controls. The existing system is basically the inertia switch main contactor and the brake and e-brake pedals and the new system (inside the brown borders).

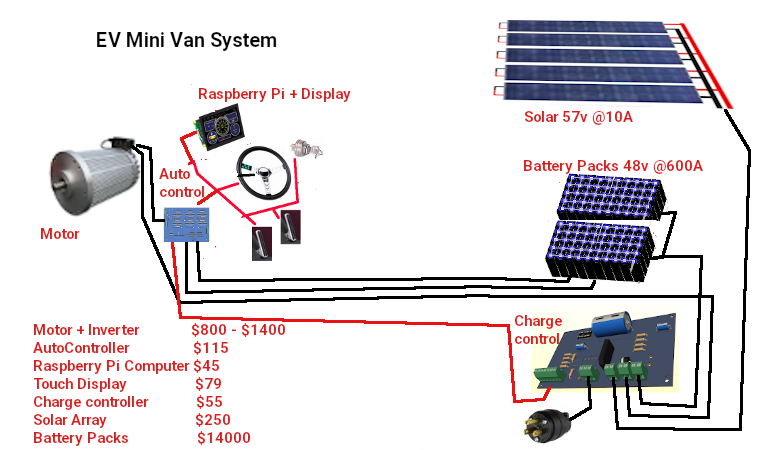

So moving left to right top to bottom we have:

So moving left to right top to bottom we have:

- *New Drive Motor, Drive Inverter,Accelerator Pedal ***it replaces the gas ICE engine and all that went with it.

- Main contactor & inertia switch, Driver control, *New Fwd/rev switch, Brake pedals ***adding a FWD/REV switch.

- *New 16x 48v blocks making 2x banks at 384v, ***replaces the Gas fuel tank.

- *New 48v, 12v taps, *New 48v Charger, *New 480 watt 48v 4A Solar array or better

- *New Dash Display, computer, GPIO, HVAC, Pwr Steer, Brake vacuum ***Cockpit control system & implements replacement systems for HVAC, Steering, Brake vacuum.

- Running lights ***Kept as is.

- 120v Shore charger.

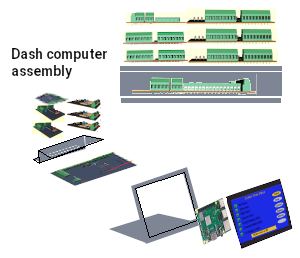

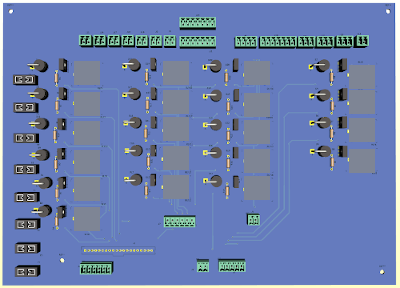

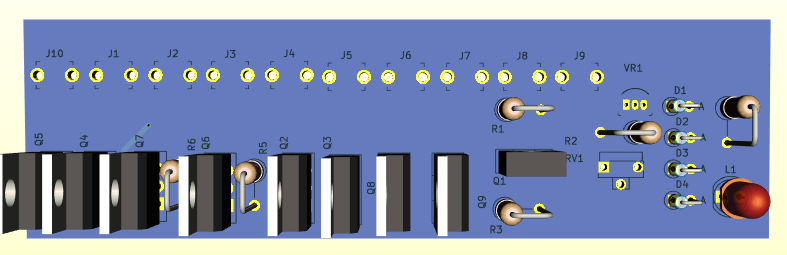

Wiring and feature pre planning

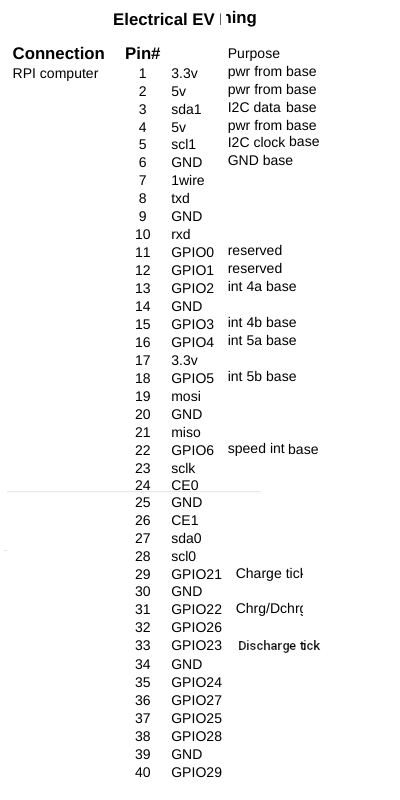

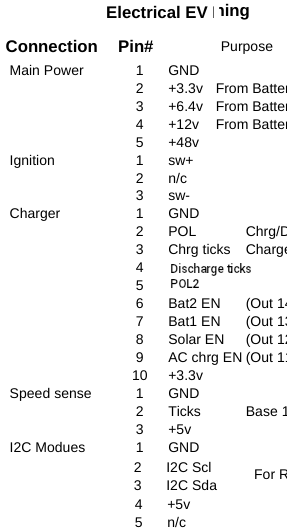

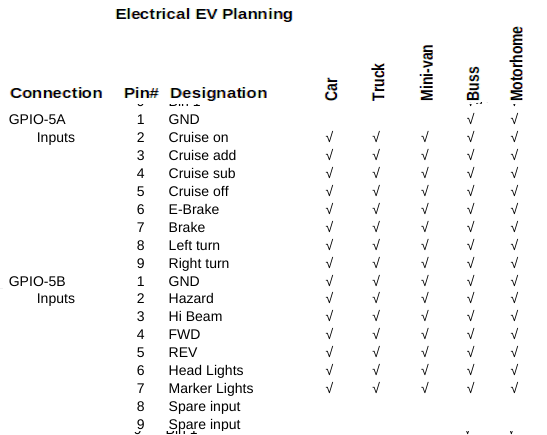

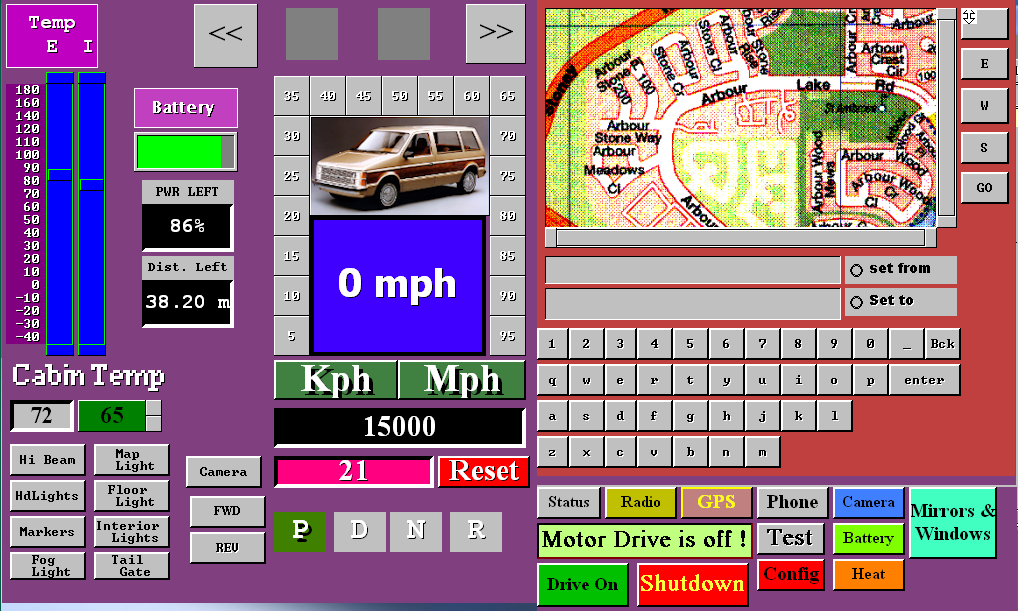

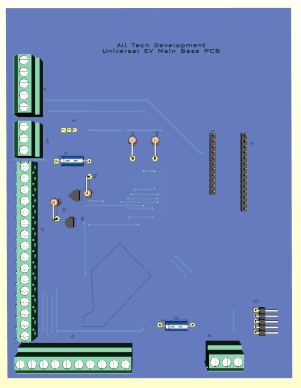

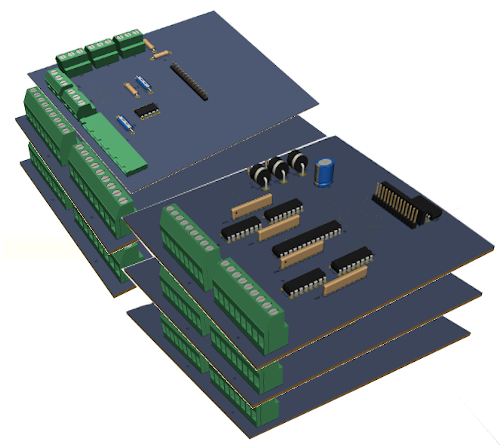

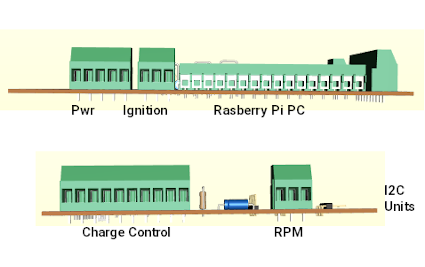

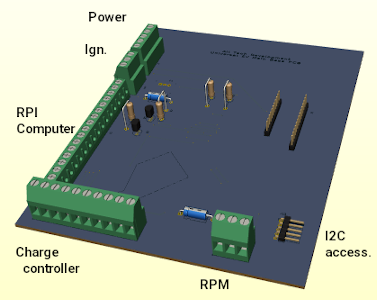

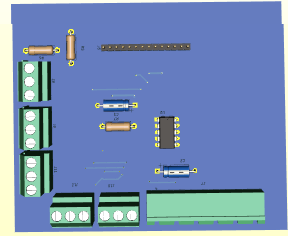

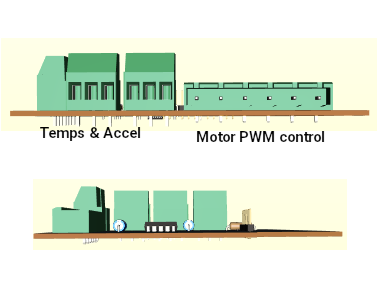

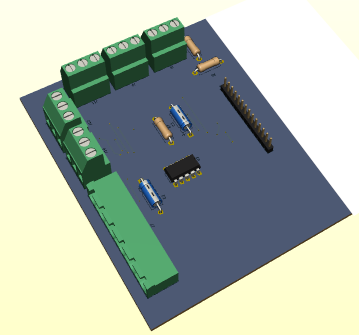

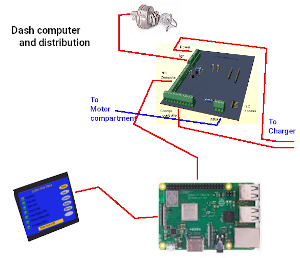

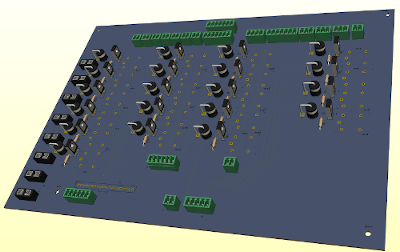

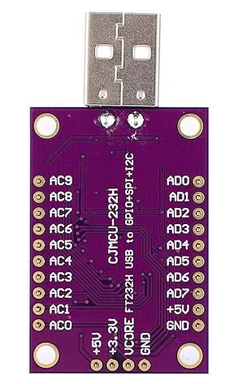

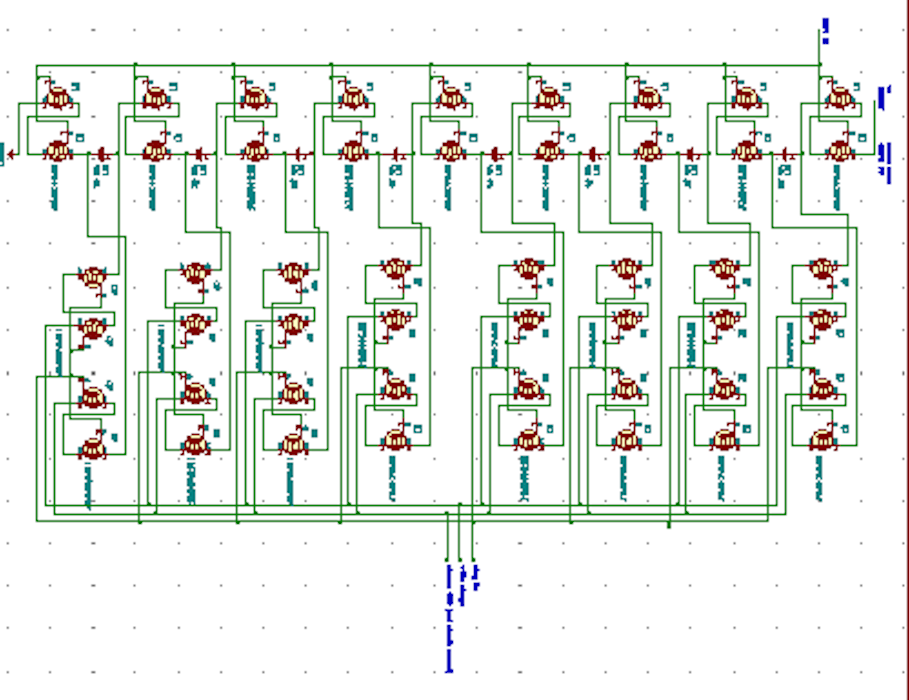

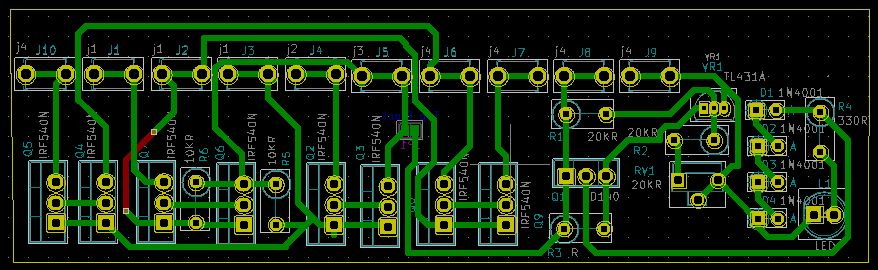

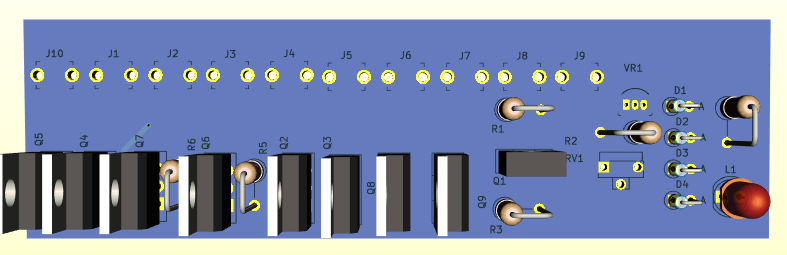

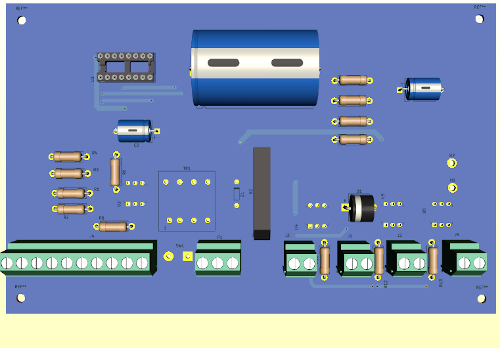

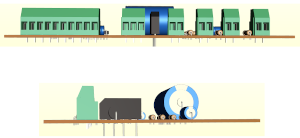

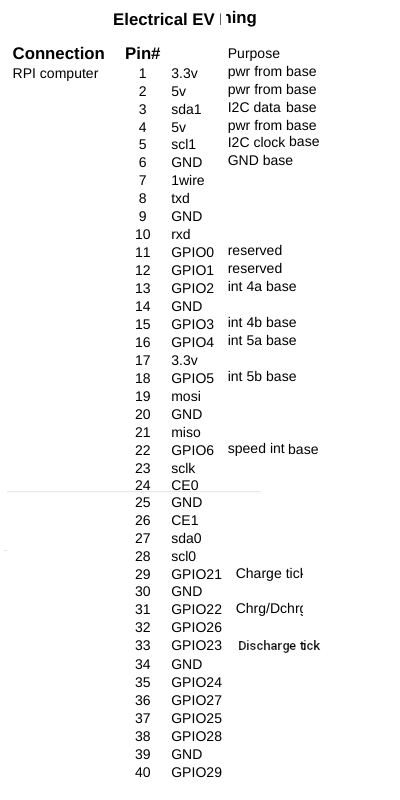

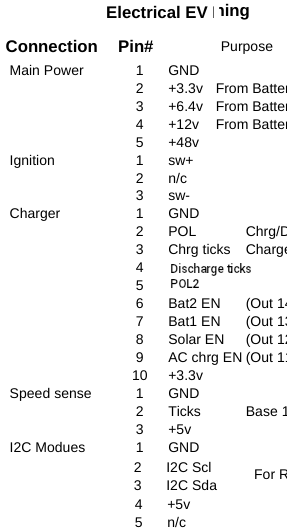

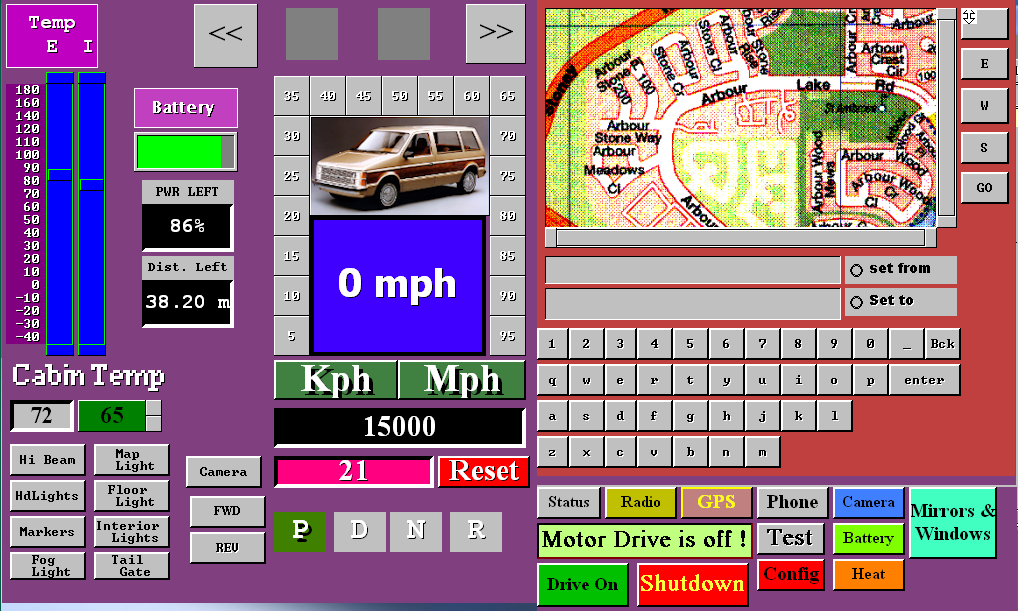

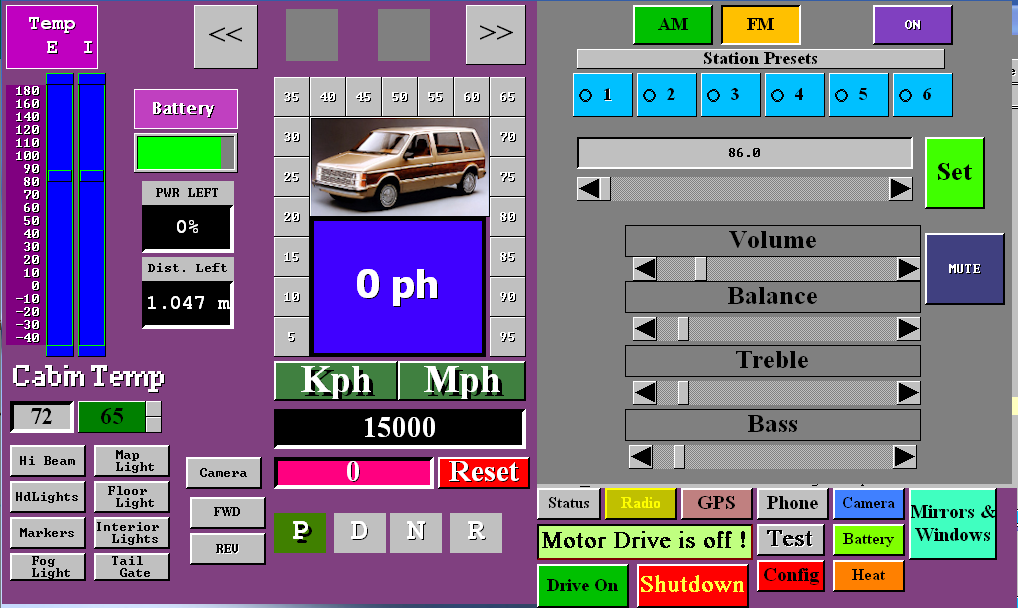

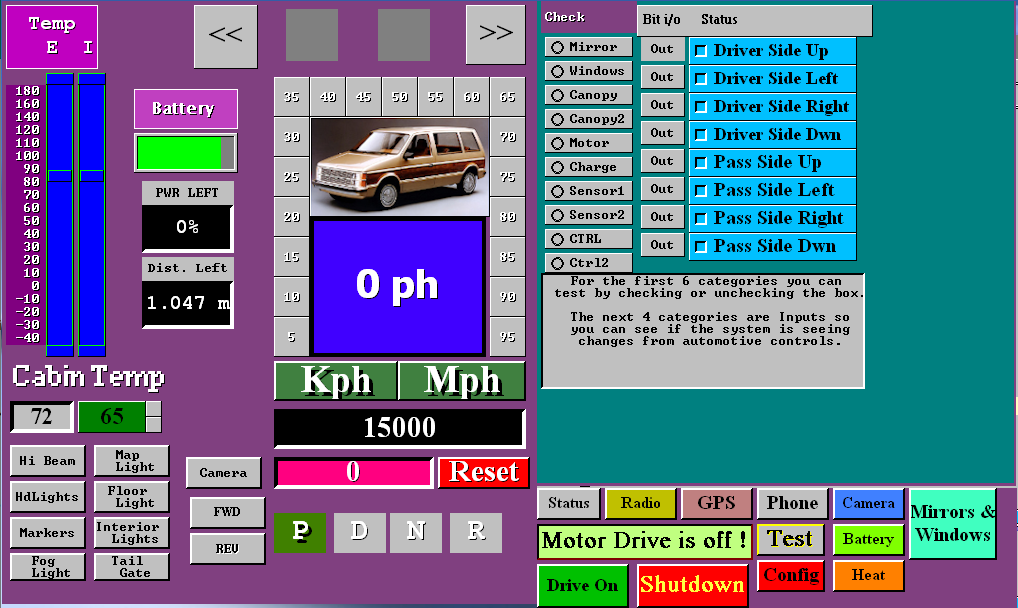

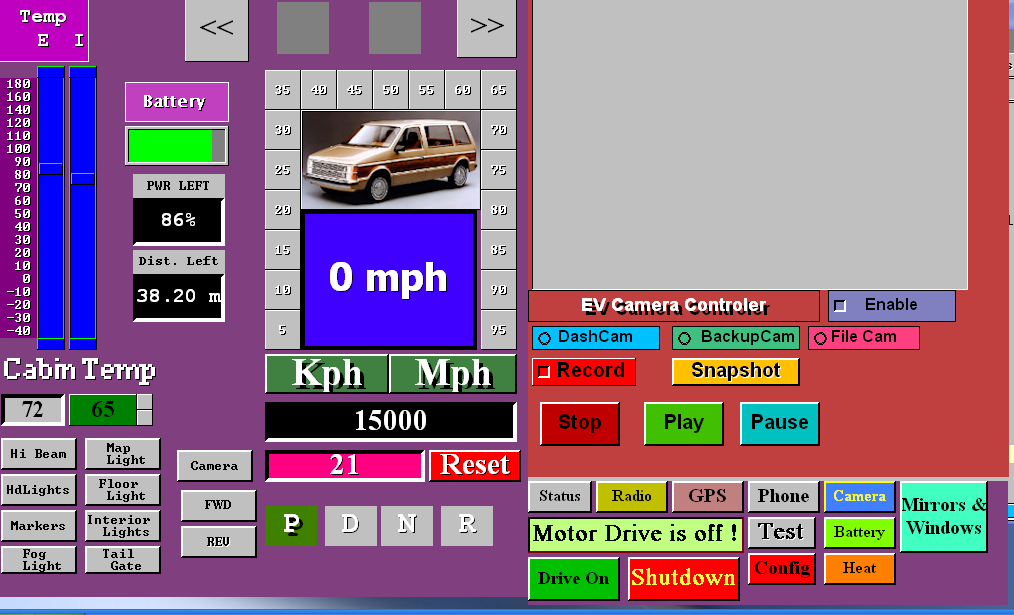

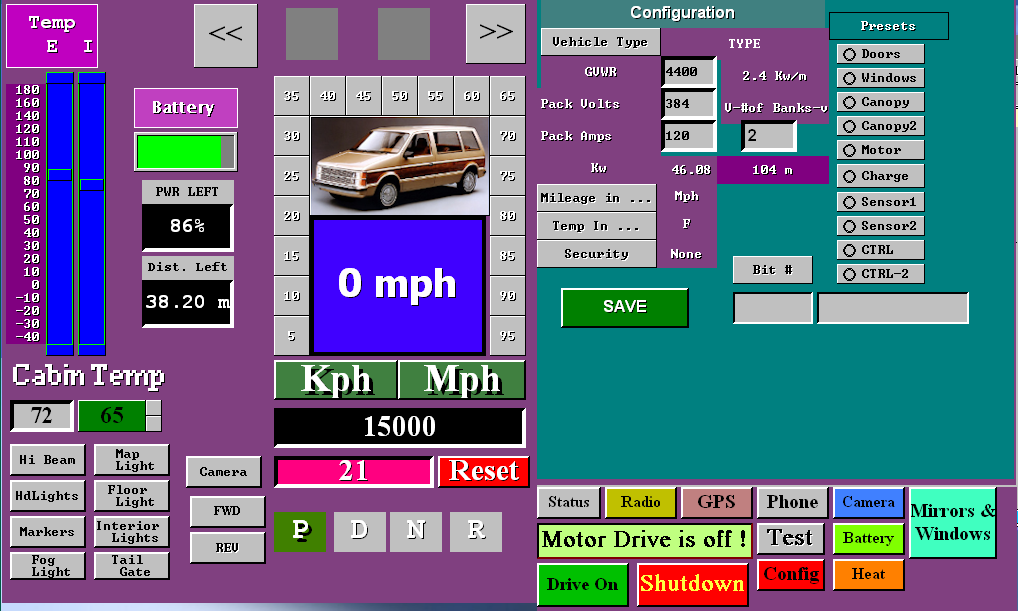

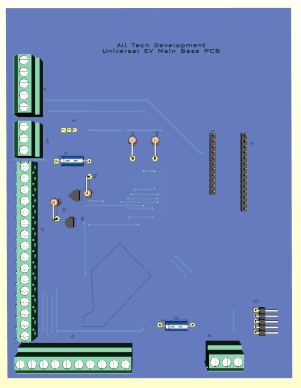

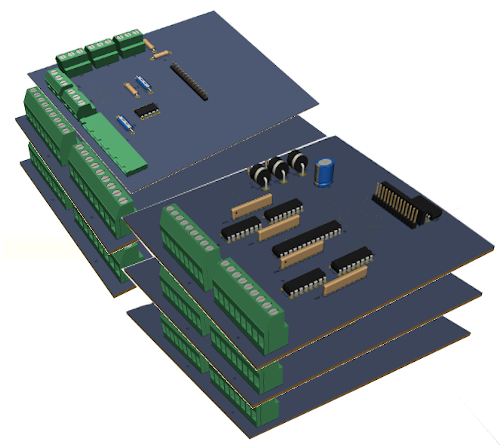

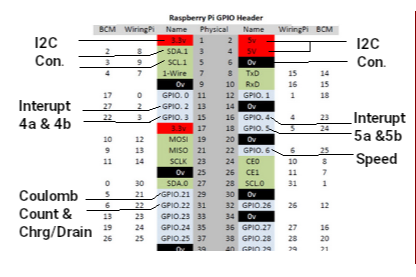

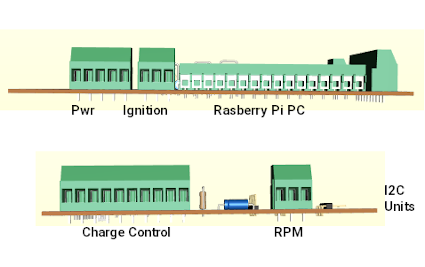

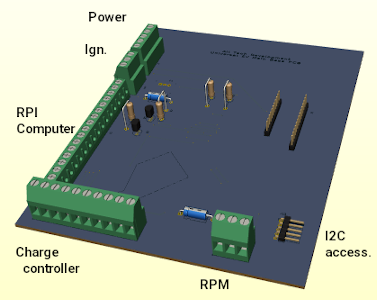

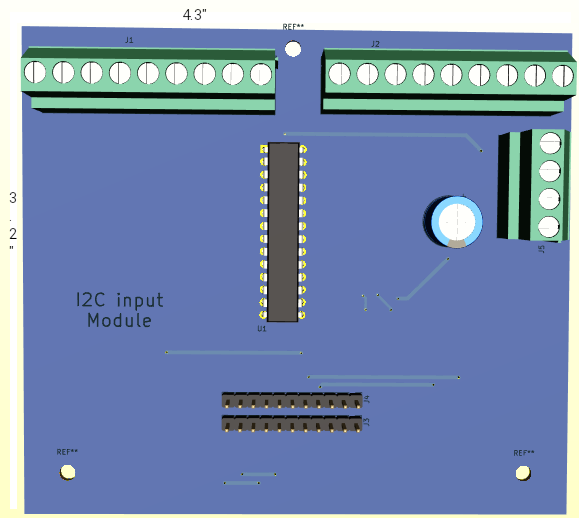

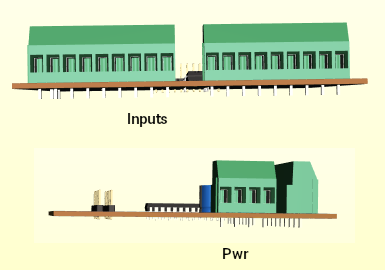

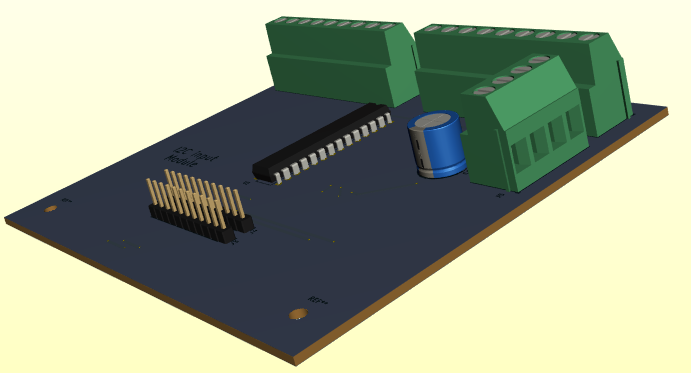

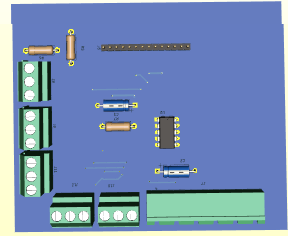

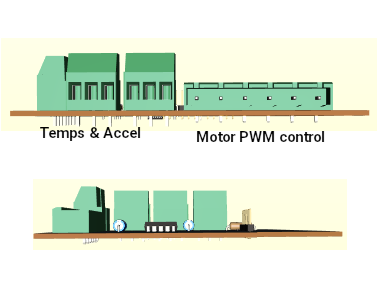

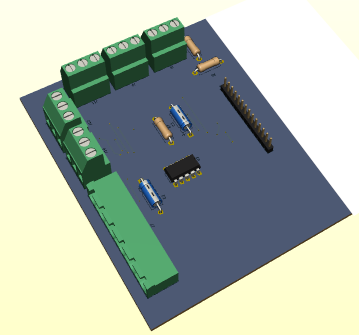

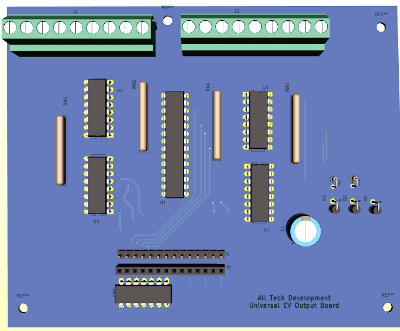

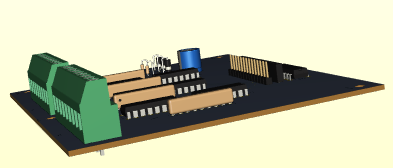

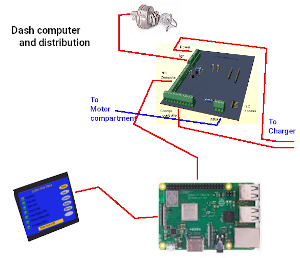

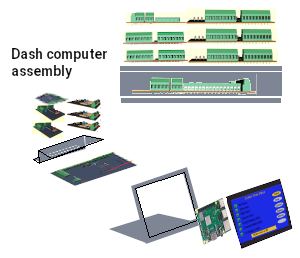

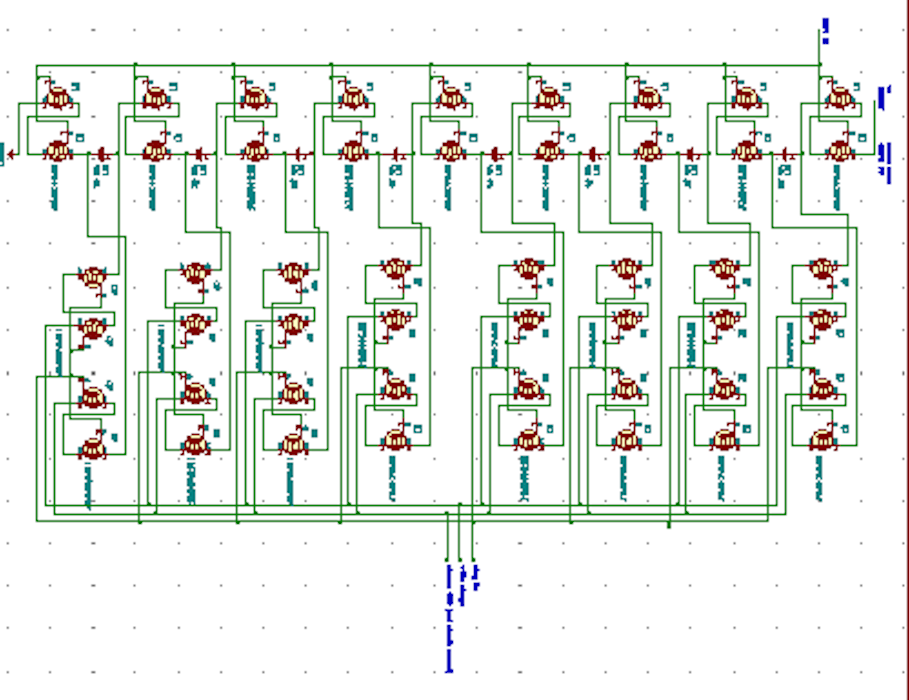

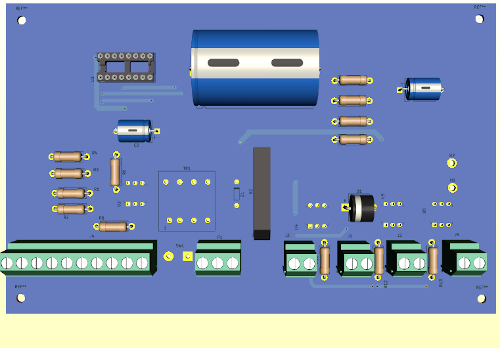

The concept here is to have an all purpose universal automotive controller and computer that can accommodate all vehicle classes from the sub-compact to the large scenic cruiser buses and Motor homes. To accomplish this the dash display has a credit card sized computer on it's back and this computer wires to a base board just behind it. The function of the base board is to supply power to the function boards, pass information to and from the computer to the various function boards, link the radio, GPS and phone into the system, and establish charge/discharge monitoring. Above the base board is 3 output modules, 2 input modules, and one analog module.

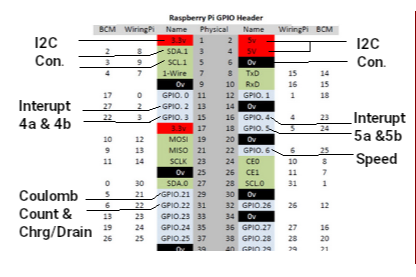

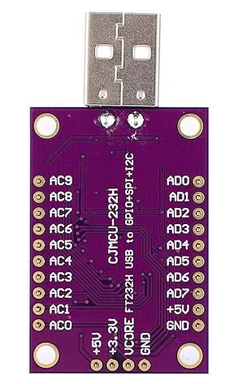

Lets start with the Raspberry Pi 3b computer. It has a 40 pin GPIO connector and we have 16 connections from the computer in use. The 16 wires pass to the 16 pin computer connector on the base board. 4 of the 16 wires supply the power, 2 operate as an I2C communication to the function boards. 4 supply notification of input changes, one

supplies real time speed of motion changes, and 4 are informing the computer about battery discharge and charge status.

Now on the base board we have a power connector, followed by an ignition switch connector. The ignition switch turns on the system and once started it cannot be shut down until the computer says it's OK. Next we have the charge controller connector that wires to the rear charge

port. Then we have a speed sensor connection. The speed sensor wires to a magnetic or optic sensor on the motor shaft. An I2C connector connects to 3 modules for radio, GPS, and Phone. Lastly, there are two connectors to the feature boards. One is 11 pins and handles all inputs to the system, the other handles all outputs and is 14 pins.

Now on the base board we have a power connector, followed by an ignition switch connector. The ignition switch turns on the system and once started it cannot be shut down until the computer says it's OK. Next we have the charge controller connector that wires to the rear charge

port. Then we have a speed sensor connection. The speed sensor wires to a magnetic or optic sensor on the motor shaft. An I2C connector connects to 3 modules for radio, GPS, and Phone. Lastly, there are two connectors to the feature boards. One is 11 pins and handles all inputs to the system, the other handles all outputs and is 14 pins.

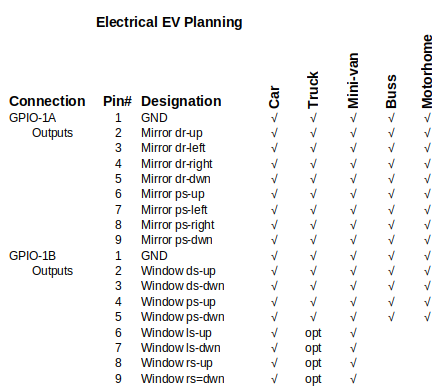

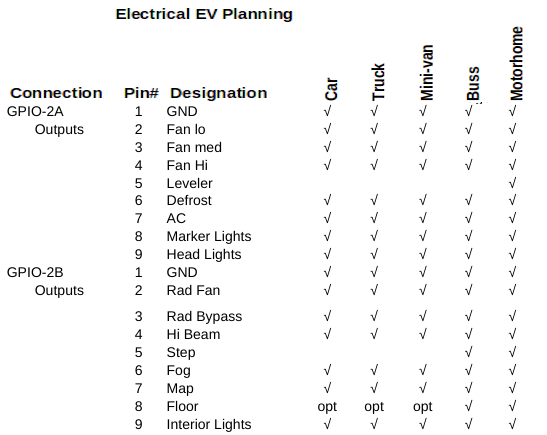

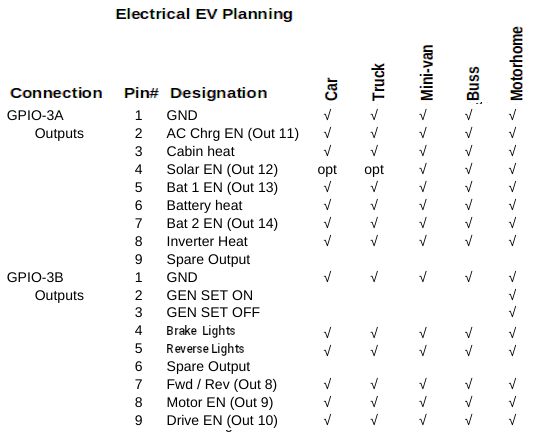

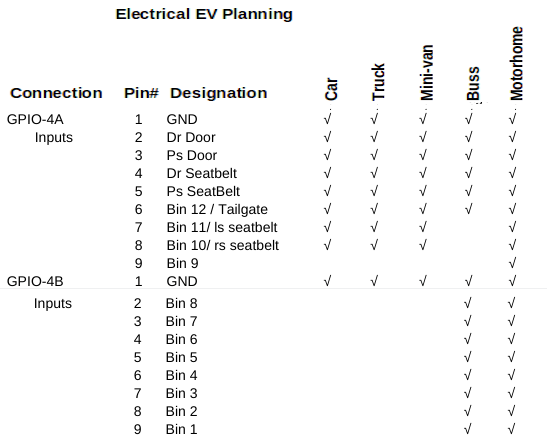

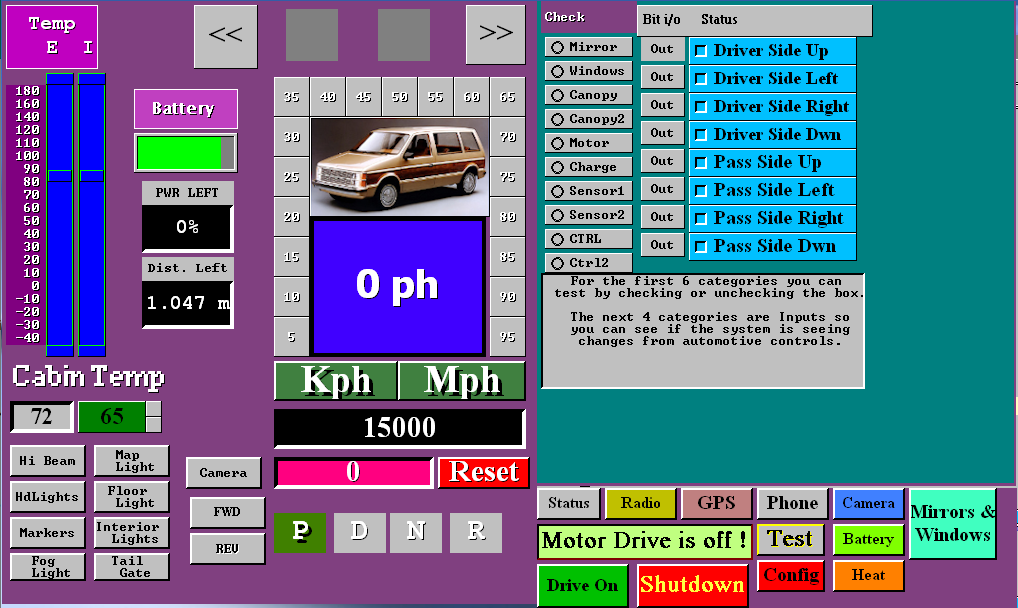

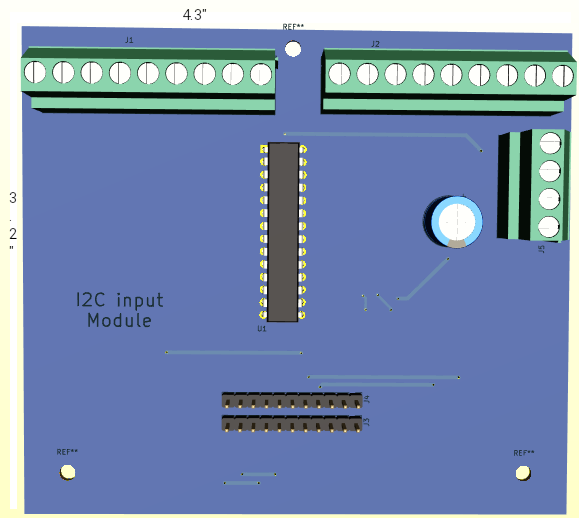

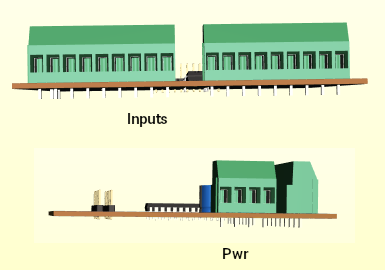

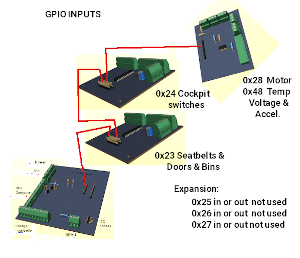

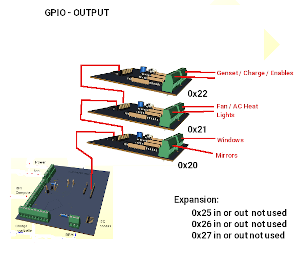

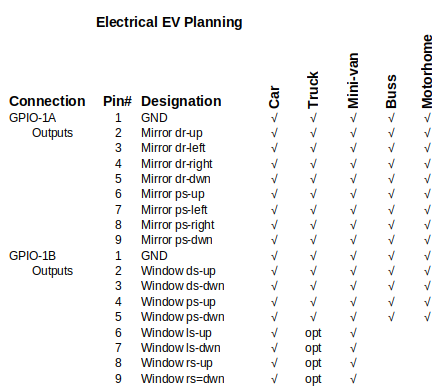

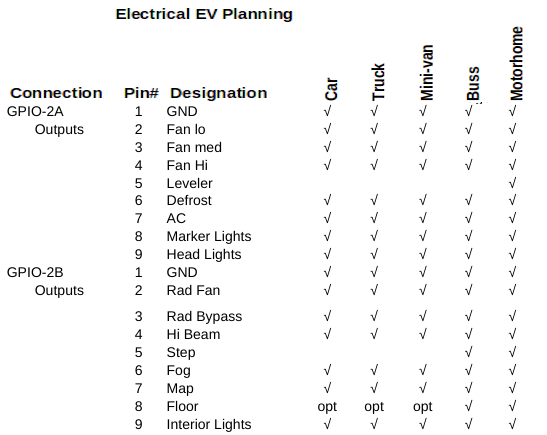

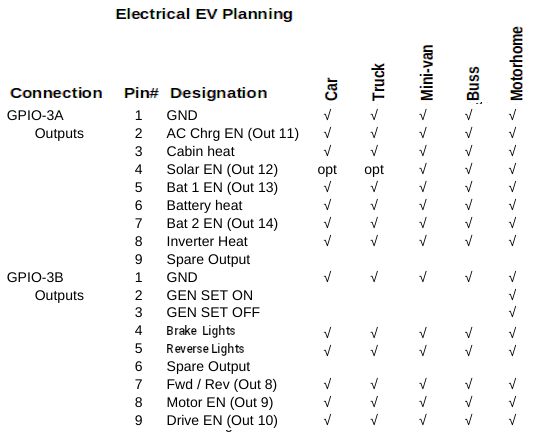

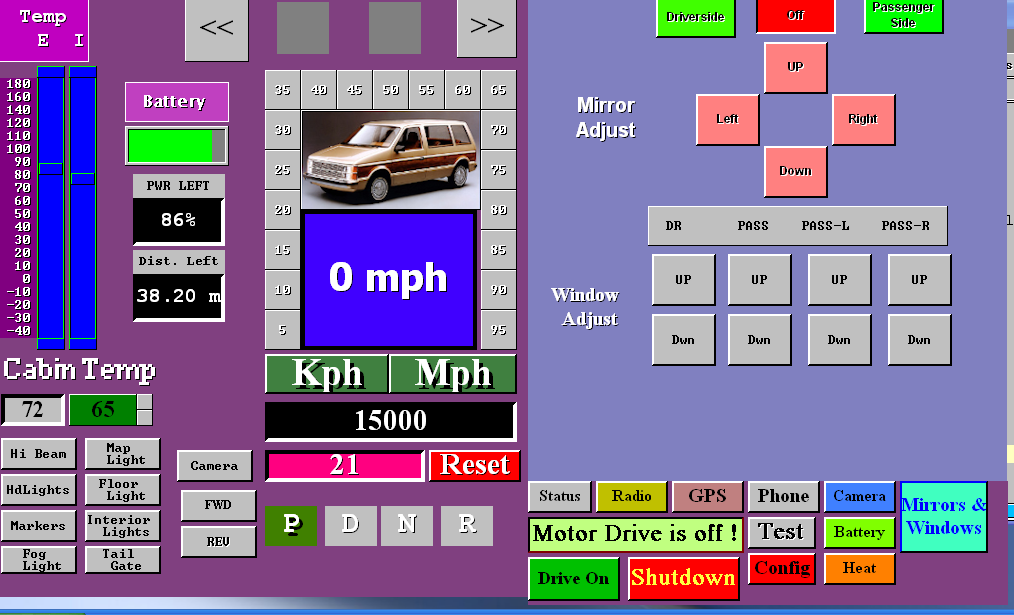

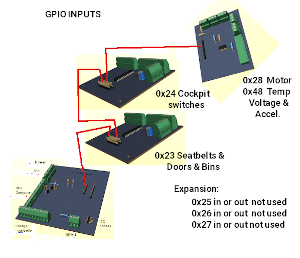

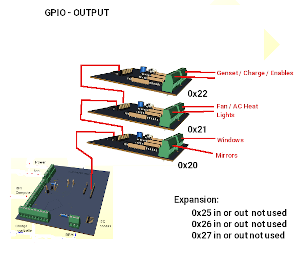

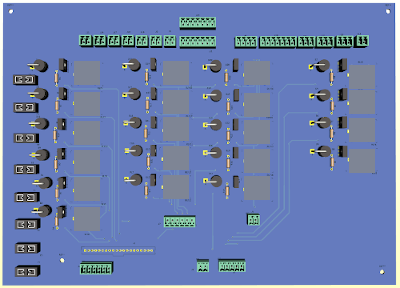

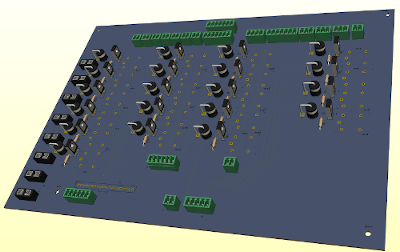

There are 3 output modules that are at

addresses 0x20,0x21,and 0x22. There are 2 x 8bit channels per module.

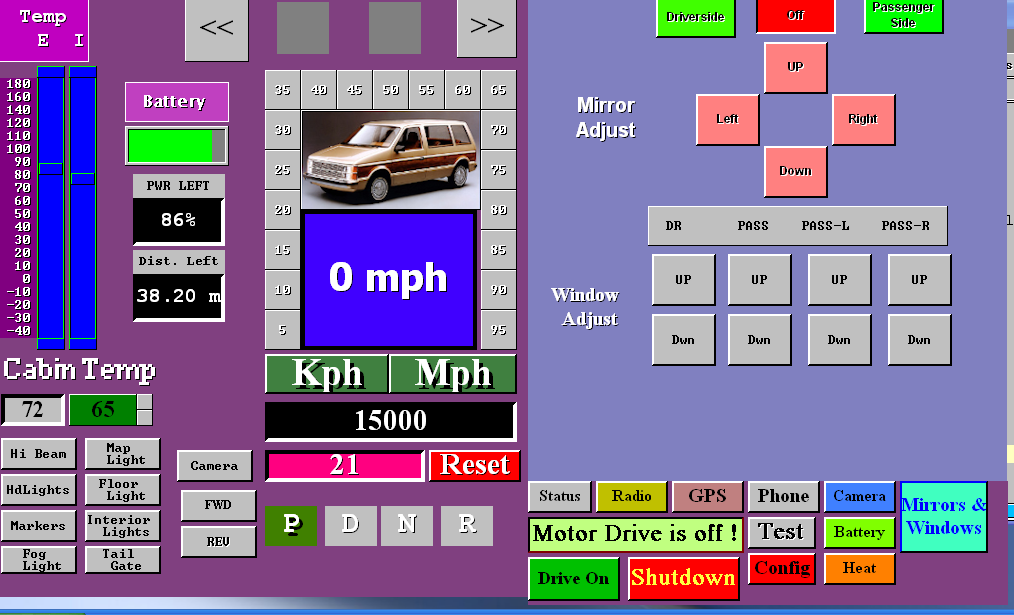

Board one is GPIO1 with channel A being mirror control and channel B being window control. Where there are provisions for two mirrors, there is provisions for left/Right front and left/right rear windows.

The second module mounts on top of first one and except for address is identical to the first. You will note that depending on the vehicle class not all bits in the channels are used. Channel one handles fan speed, defrost, AC, turning on/off the lights and in the case of motor home the leveling jack power. The second channel controls the rad fan, and rad bypass to help control motor cooling, more lights, and in the case of a motor home, the entry step.

The last output module again is at a different address but this time has marks like (Out 11) that identify output states that either go to the ADC board for motor control or to the base board for charge control. Channel A handles charge Enables and cabin, battery, and Inverter heating (for cold weather). Channel B has provision for a Gen Set on a motor home, and motor related Enables. and that's it for outputs.

Drive-En has special meaning. First this signal in software prepares the vehicle to be driven. The control signal passes to the traction inverter to turn it on and it also enables the brake vacuum pump, power steering pump and h20 pumps so they are ready as soon as there is a call to move the vehicle.

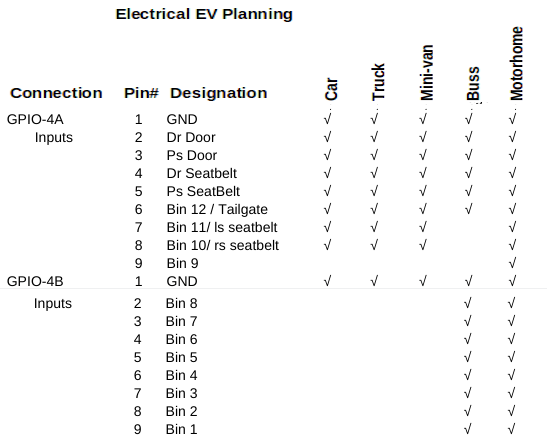

Board 4 starts the input side of things. Channel A informs the computer of the status of doors, seat belts and bin doors. Channel B deals entirely with bin doors.

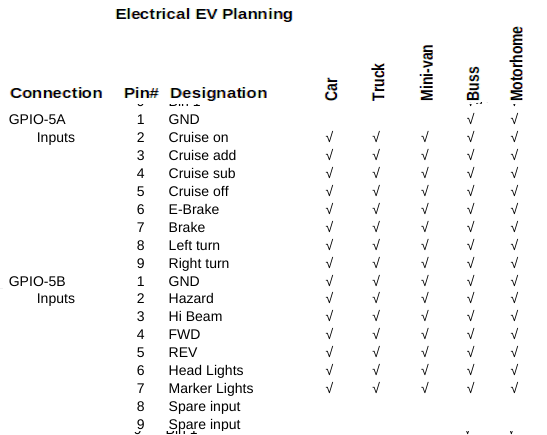

Board 5 is the last input board in terms of digital inputs. It wires to the cockpit switches for Cruise, brake and E-Brake, left turn, right turn, Hazard, hi-beam, headlight, marker lights, and the fwd or reverse sswitches. If the gear shift is in neutral or park it is neither fwd or reverse.

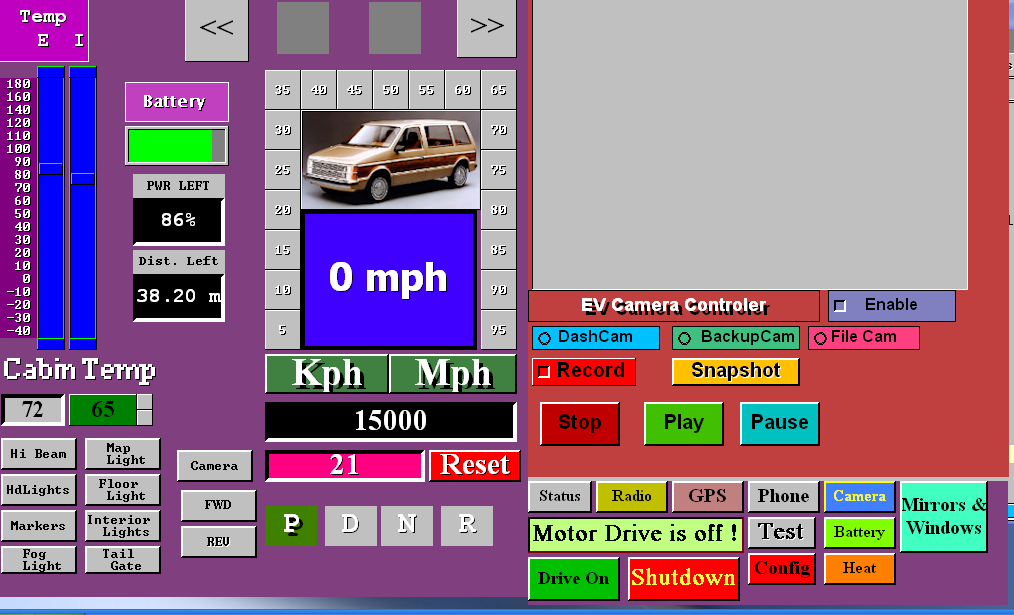

The final module is the ADC module with reads the accelerator pedal, the battery voltage and the temps on one side and controls the motor Inverter on the other side.

Canopy Systems

The cooling, steering, braking

systems and lighting management resides up front in the canopy along with the Motor and Inverter control. As designed, we have Motor Control (Drive-En, Motor-En, RPM value) coming from the ADC board. We also monitor Inverter and Motor temp from the ADC board. We can control the Rad fan and Rad bypass using GPIO-2 outputs and can also heat the Inverter and Motor using GPIO-3 outputs. The base PCB collects rpm ticks from the sensor on the motor shaft.

GPIO-2 supplies Left-turn, Right-turn, Markers, headlight, Hi-Beam, and Fog lights. These signals are designed to operate 48v 0.02A LED light systems. If the plan is to use 12v incadencent bulbs, 10A relays will

be needed. The steering pump, brake vacuum pump and water pump must connect to 12v using Drive-En signal so that operation is on when intending to move the vehicle. The headlight and high beam must use a relay. If motorhome application, the leveler output also needs a relay for the leveler pump. The Brake lights and reverse lights and trailer lights, while not part of the canopy systems will be in the canopy. We added an output to the above specs for sending signals to turn on and off brake lights and reverse lights. In an ICE design water pump, brake vacuum, and pwr steering are the result of the Engine running and in our case will be the result of Drive-En signal since the motor only turns when moving.

Cockpit Systems

In the cockpit with the driver will be the brake (and switch), E-Brake (and switch), Key switch, a Forward / Reverse switch, and the Potbox (accelerator). None of the high Voltage or High current comes into the vehicle. The dash computer monitors everything. The ignition is locked to on even if the key is removed. If an incorrect password is